Chod in Limitless-Oneness

Dr. Yutang Lin

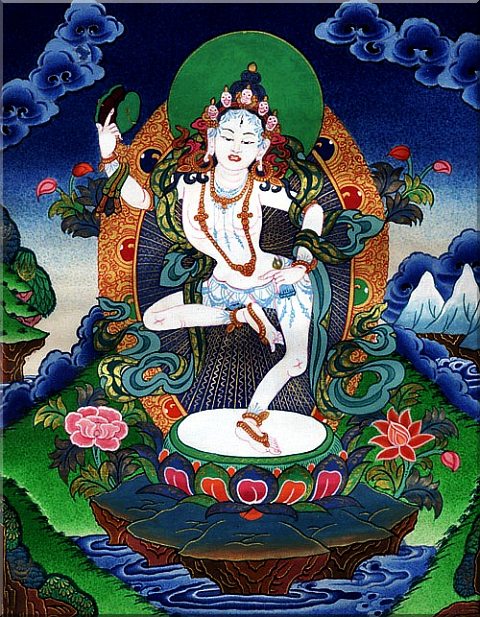

Thangka of Machig Labdron

Tantric

Disciple Yutang Lin

Cutting

through attachment to body to offer compassionate sacrifice,

In wondrous application of wisdom and compassion all things unite.

Intangible non-self, though hard to grasp, is given a practical shortcut.

Originating a Tantric path to feed back

Comment:

Tibetan

lady patriarch Machig Labdron originated the tantric practice of Chod, and

thereby enabled the practice and attainment of intangible non-self through

cutting down the attachment to body. (See my work, "Chod in

Limitless-Oneness.") This is the only tantric Buddhist practice that was

originated in

Written

in Chinese on April 4, 2001

Translated on April 5, 2001

Preface

Chod,

meaning cutting through, is a Buddhist tantric practice. In Tibetan Buddhist

Tantra it is taught to beginners for accumulation of merits; it is also practiced

by ardent devotees for realization of Dharmakaya—the pinnacle of Buddhist

realization. How could one practice be so common and yet profound? Its original

teacher, Machig Labdron (1055-1153), was a Tibetan lay lady, a very rare

phenomenon in the history of Tibetan Buddhism, and for generations up until

now, her serious followers are mostly wondering beggars and yogis. Chod as

formulated by Machig Labdron is the only Buddhist tantric practice that

originated in

The

fact that Chod is a practice for both beginners and advanced yogis drew my

interest in writing the present exposition. For the general public who are intrigued

by the mysterious aspects of this practice and its lineage, an explanation in

layman's terms will be offered, and some related topics will be discussed. For

serious Buddhist practitioners the philosophical significance involved in this

practice will be brought to light. In particular, the significance of Chod in

the light of Limitless-Oneness will be explained. This is completely in

accordance with the spirit of Chod, as it was labeled by Machig Labdron to be

the Chod of Mahamudra.

Yogi

Chen, my late Guru, taught me how to practice the Chod ritual written in

Chinese by him. I was very impressed by the profound meaning and open

perspective conveyed through the ritual text. Now that I am writing on Chod, I

take the opportunity to introduce it to readers who do not read Chinese. My

translation of the ritual is included in this work as an independent chapter.

My sincere thanks to Stanley Lam and Chen-Jer Jan for the corrections,

improvements and suggestions they made to this translation.

In

1955, with the help of an interpreter, Yogi Chen translated from Tibetan into

Chinese a version of An Exposition of Transforming the Aggregates into an

Offering of Food, Illuminating the Meaning of Chod. This book was printed in

1983 for free distribution. Now it has been revised by me and included in

Volume 17 of The Complete Works of Yogi Chen. The Chinese titles of these two

works are listed in the References at the end of this book.

During

the course of my preparation for this work I have received teachings in a dream

that Chod is not only an antidote to attachment to body but also one to all

five poisons, i.e., greed, anger, ignorance, arrogance and doubt. Again, in a

dream state I saw a curved knife cutting through my joints and brought

relaxation to those areas; thus I was blessed with and taught about the

releasing effect of Chod.

Furthermore,

one day as I slept I saw the following Chinese Characters:

![]() 鈴

鈴

將此譜傳下去

The

word元(yuan) means the origin, and the word鈴 (ling) means bell. In the tradition of

Chod there are eight pairs of teachings and lineages, hence I interpret the

character formed by two元, which does not exist in

Chinese, to signify the origin of all these pairs of traditions, and in tantric

context the bell refers to the Vajra Bell which represents the Dakinis.

Therefore, this phrase denotes the Founder Dakini, Machig Labdron. The second

set of characters forms an imperative sentence, commanding: Pass down this

record! The character譜(pu) is

usually employed to denote a lineage record. Hence in this context the meaning

is clearly: Pass down this lineage (record)! To me, this is a clear sign of

approval from the Great Mother, Machig Labdron.

I am

grateful for all the teachings and blessings, including those not mentioned

here, that have been bestowed on me for my humble service to the glorious

tradition of Chod.

No

matter how marvelous a practice is, if one does not have the determination to

adopt it as a regular activity and persist in learning through it, there would

be no significant results whatsoever. I hope that this work of mine would have

illustrated the wondrous aspects and functions of Chod, and provided enough

clarification to motivate and improve its practice. May readers of this work

gain real and ultimate benefits of Chod through regular and persistent

practice!

Thanks

to comments from Chen-Jer Jan I have added some clarifications to this book. I

am also grateful to Stanley Lam for formatting the entire book for publication.

Yutang

Lin

July 6, 1996

A Study for the Cultivation of Harmony

I. General Introduction

1.

The Body and Spiritual Quests

The

condition of one's body is a major factor of one's enjoyment or suffering in

life; and one's existence is usually understood to be determined by the

subsistence of one's physical life. Consequently, preservation of our physical

existence and promotion of our physical well-being is at the heart of most

human endeavors. From such motives and activities it is inevitable that

self-centered prejudices and selfish practices become dominant and customary.

Since

our physical existence and well-being is dependent upon many factors, and many

conditions in life, of natural or human origin, are beyond human control,

suffering and death are lurking like traps and land-mines. Suffering in our

lives is further compounded by everyone's self-centered prejudices and selfish

practices. In order to promote selfish interests people often go to the extent

of ignoring or sacrificing others. Wars and fighting are waged at almost every

corner and every level of human existence.

To

free us from such seemingly insoluble miseries the fundamental approach is to

learn about and practice freedom from self-centeredness. Only then can we see

clearly that living in the spirit of cooperation and empathy is a far more

sensible approach to life. To become free from self-centeredness our

preoccupation with the body and its well-being need to be reexamined and

readjusted in an all-round view of life. As a result of such reflections, many

spiritual practices consider a simple way of life as a prerequisite.

In

addition to our physical conditions, our spirituality is also a major factor of

the quality of our lives. No one can be happy without harmony between physical

and mental states. The growth of one's spirituality is intimately connected

with how one faces and utilizes one's mental states as well as one's physical

situations. Goals of spiritual quests usually involve unity of the mind and the

body and transcendence of the physical existence. Transcendence in spirituality

will be achieved only after one's mentality is no longer bound by one's

physical conditions and environment.

Due

to the intimate connection between the physical and spiritual aspects of one's

life, spiritual practices often involve physical training. Most of these

consist of posture, breathing and simple maneuvers. There are also yogic

exercises that are very difficult, and it often takes years of training to

attain such performance. To transcend considerations originating from the root

of one's physical existence, the body, there are ascetic practices that punish

the body to achieve self-mortification or self-denial. Self-sacrifice of the

body through offering of physical or sexual services, or even donation of

organs, is also sometimes used as a spiritual practice. Practices involving

punishment or self-sacrifice of the body are rarely adopted, and due to their

extreme nature may lead to unintended consequences.

2.

Buddhist Teachings Related to the Body

On

one hand, Buddhist teachings point out that attachment to the body and

identification with one's physical existence is the main source of suffering,

while on the other hand, respect for life is also clearly taught by stipulating

no-killing as one of the five basic rules of conduct. The Buddhist teaching

emphasizes no killing of born and unborn lives of human beings as well as of

other sentient beings. A popular Buddhist practice is to save endangered lives

such as birds, fish and animals in captivity and release them back to nature.

Respect

for life and recognizing the body as the root of suffering are not

contradictory. Destroying the body and putting an end to this life would not

resolve the misery of conditional existence because the consciousness of a

sentient being will continue to transmigrate in the cycle of endless living and

dying as long as grasping to the notion of a self lingers. Killing of others or

oneself will in itself become a major cause leading to more suffering in this

and future lives. The body can also serve as an instrument for attaining the

liberation of oneself and others from transmigration. The key to transforming

the status of the body from the root of suffering to an instrument for

liberation lies in one's ability to recognize and renounce one's blind and blinding

attachment to the body as the embodiment of the self which is illusive and

unattainable upon philosophical analyses.

Buddhists

do use medicine to heal themselves of diseases, do clean their bodies, houses

and gardens, and in so doing killing of micro-bacteria, insects and mice is

often inevitable. Are Buddhists hypocritical in accepting no-killing as a basic

rule of conduct? These kinds of activities, although involving killing of

sentient beings, are aiming at the protection of human lives without a malice

to kill other beings. Before such actions are taken a Buddhist would try with

every effort to avoid killing unnecessarily and look for alternatives. When

such killing is unavoidable, it is done with repentance and prayer for a better

rebirth for the victims.

As

recorded in biographies, some advanced Buddhist practitioners would sacrifice

their bodies willingly to feed hungry mosquitoes or even tigers. When Sakyamuni

Buddha in one of his previous lives offered his only possession, his body, to a

hungry tiger he did not intend to commit suicide but simply to alleviate the

tiger's hunger. Thus it is clear that the teachings of no-killing and

compassion for all beings are taken seriously by Buddhists. The extent to which

one is able to harmonize such a rule of conduct and the ideal of compassion for

all beings varies with individual efforts and devotion.

The

discussion presented in the last two paragraphs clearly demonstrates that a

practitioner's intention may be simple but due to the circumstances his

practice may become a complicated matter from various points of view. Putting

Buddhist teachings into practice in real-life situations is therefore not a

easy matter. My humble opinion is that a Buddhist practitioner should maintain

a pure motivation, aiming at the Enlightenment of all beings, and learn how to

practice in daily life through experiences. Just as a Chinese proverb says,

"As one grows older, one keeps on learning more." (活到老,學到老。)

Buddha

taught the middle way which points out that neither asceticism nor hedonism is

the right path toward liberation. He used the analogy of a stringed instrument

which can produce melodies only when the strings are neither too tight nor too

loose. Hence, the body as an instrument for achieving liberation from transmigration

should be properly taken care of. However, as an antidote to past indulgent

behavior patterns or as a horsewhip to push forward one's spiritual endeavor,

ascetic practices are sometimes adopted by some devoted and diligent Buddhist

practitioners.

In

Asian Buddhist countries some monks or nuns would undertake the ritual of

Burned Scars of Sila Commitment. By enduring small piles of incense burned on

top of one's shaven head or arm, permanent scars are left as a sign of one's

devotion and vows. Some would even burn one or more fingers over candle flames

as offering to Buddha. Although these are practices adopted by Buddhists, they

lack proper Buddhist explanation and origin. It is said that the custom of

Burned Scars of Sila Commitment was initiated in

In

tantric Buddhism it is emphasized that the body is the residence of Buddhas and

the very instrument through which to attain Buddhahood. Hence, one of the

fundamental rules of conduct for tantric practitioners is not to have disregard

for the body. This is not the same as cultivating attachment to the body. The

usual attachment to the body is due to grasping of a self and its subsistence.

The tantric teaching on proper caring of the body is with the understanding

that self is an illusion and that with proper training the body may help one to

realize the selfless nature of all phenomena.

Many

Buddhist teachings center around the body. The practice of chanting a list of

thirty-six impurities, referring to all the various parts of the body, aims at

reminding oneself of the body as a collection of undesirables. Observation and

visualization of the various stages of a decaying corpse is a practice both for

reminding oneself of impermanence and for reducing one's unreflective

attachment to sensual objects. Visualization of a skeleton is a practice for

purifying one's greed. Being mindful of one's sensations, feelings, breathing

and action is also taught as meditation practices. To advance on the

Bodhisattva Path almsgiving of wealth, services, knowledge, teachings, and even

bodily parts are encouraged. In tantric Buddhism a Yidam body is maintained in

visualization instead of one's physical body. Chod, the main topic of this

work, is a tantric practice which involves visualization of the offering of the

body. In highly advanced tantric practices sexual activities are employed to

experience the selfless nature of ecstasy which is free from the stains of

jealousy, obsession, possessiveness, greed, attachment, envy, etc.

It

is interesting to note that among Buddhist teachings which revolve around the

body, there are various attitudes toward the body. Some consider it as an

object of impurity, some the root of self-centeredness, some an object of

fundamental attachment, some an object for the practice of mindfulness, some an

object for the practice of almsgiving and offering, some an object to be

meditated away in Sunyata, some an instrument for enlightened experiences, and

some the abode of Buddhas. This illustrates the relative nature both of the

functionality of the body and of the Buddhist teachings revolve around it. All

these views, teachings, functions and practices may coexist in harmony as long

as their respective functions in guiding toward Enlightenment are thoroughly

understood and adopted accordingly.

II. Chod─the Tantric Practice of Cutting through Attachment

Chod, meaning cutting through, is a Buddhist Tantric practice. Although it is

rooted in Buddhist teachings transmitted from

1.

A General Characterization of Chod

Recognizing

the body as the root of one's attachment to self, Machig Labdron formulated

Chod to be a practice that would destroy this fundamental attachment and

simultaneously develop compassion for all beings. The main part of a Chod

practice can be outlined as follows:

A.

Transfer one's consciousness into space and identify it with the black Vajra

Yogini.

B.

Through visualization, identify the body with the universe and then offer it

completely to all beings who would want them, especially one's creditors,

enemies, and evil beings.

For

details, please refer to Chapter III below for an example of a Chod ritual.

To

handle worldly or spiritual problems there are many types of approaches. Some

try to dissolve the problems, some plan to escape from the problems, some

attempt to stay at a safe distance and tackle through theoretical discussions,

and some would face the problems and work on them. When one is not ready to

handle the problems, the first three types of approaches are temporarily

appropriate; nevertheless, the ultimate test of a solution lies with the

head-on approach.

Chod

is obviously a head-on approach to the spiritual problem of subconscious

attachment. It also exemplifies the ultimate wisdom of facing the reality to

realize its conditional nature instead of being satisfied with merely

conceptual understanding. Chod is learning through enacting. One's attachment

to the body, fear of its destruction, greed for its well-being, and displeasure

for its suffering are all put to test in a Chod practice. When all these

subconscious mental entanglements are brought to light through the

visualization of dismemberment, one is really fighting with one's self. No one

who cannot pass the test of such visualizations would have a chance of

achieving liberation under real-life circumstances.

Advanced

Chodpas (practitioners of Chod) do not satisfy themselves with just the ritual

practices. They often stay in cemeteries, desolate places, and haunted houses

in order to face the fearful situations and experience the interference from

desperate or evil spirits. By developing compassion for all beings, including

those trying to scare or harm them, by sharpening wisdom through realizing the

non-substantial nature of fearful phenomena and fear itself, and by deepening

meditation stability through tolerating fearful situations, Chodpas gradually

achieve transcendence over attachments, fear, greed, and anger. Through the

hardship of direct confrontation they advance, step by step, on the path toward

Enlightenment.

The

separation of the consciousness from the body indicates the mistake of

identifying with the body. It is the aboard of this life; both this life and

its aboard are transient and cannot be grasped for good. The identification of

the consciousness with the black Vajra Yogini signifies the recognition of the

wisdom of non-self. On one hand, the black Vajra Yogini is a manifestation of

the primordial wisdom of non-self; and on the other hand, due to the non-self

nature of both the consciousness and the Yogini, they may be identified.

Furthermore, the identification with the black Vajra Yogini, as it is the case

in all tantric identification with a Yidam, is not grasping to a certain image

but involves salvation activities. In other words, it is a dynamic approach to

personality changes.

On

the surface Chod seems to be an offering of only the body. Nevertheless, during

the visualization the body has been identified with the universe, and

consequently the offering means the offering of all things desirable. Thus,

Chod is not just aiming at reduction of attachment to the body but also of all

attachments. In terms of the traditional tantric classification of four levels,

Chod could be characterized as a practice which frees one: outwardly from

attachments to the body; inwardly, to sensual objects; secretly, to all desires

and enjoyments; and most secretly, to self-centeredness. A Chodpa would

gradually experience the transforming effects of Chod practices and become

aware of its ever deeper penetration into the subtle and elusive core of one's

attachments.

2.

The Essential Ingredients of Chod

Chod

as a tantric practice consists of the following essential ingredients:

A.

The Blessing of the Lineage

In

Tantric Buddhism lineage, meaning an unbroken line of proper transmissions of

the teachings, is essential to practice and realization. This is because what

is transmitted is not just the words but something spiritual and special.

Through proper transmissions the blessings of all the generations of teachers

are bestowed on the disciples. Without such blessings no one can even enter the

invisible gate of Tantra. Tantric practices without the blessing of lineage may

be likened to automobiles out of gas.

In

Tantric Buddhism lineage is always emphasized and the teachers are revered as

the root of blessings. In Sutra-yanas the importance of lineage is often

overlooked by scholars who lack interest in practice and ordinary Buddhist

followers. This is probably the main reason why in Tantric Buddhism blessings

can often be directly sensed by practitioners while in Sutra-yanas such

experiences are less frequently encountered.

All

tantric practices derive their special effectiveness from the blessing that is

transmitted through the lineage. In the case of Chod, the blessing from Machig

Labdron is the source of such blessings. All other teachers that form the

various lineages of Chod are also indispensable to the continuation of these

lineages; without their accomplishments and devoted services to the Dharma, the

teachings would not be still available today. Therefore, we should remember

their grace and always hold them in reverence.

To a

practitioner who is fortunate enough to have received the blessings of a

lineage, the meaning of lineage becomes his devotion, with all his heart and

soul, to carry on, to preserve and transmit the teachings for all generations

(of disciples, the real beneficiaries,) to come.

B.

The Wisdom of Recognition and Transformation

Self-clinging

is the fundamental hindrance to Enlightenment and the fundamental cause of

transmigration in samsara. Although it is the main obstacle for a Buddhist

practitioner to eradicate, its subtle nature and elusive ways are beyond easy

comprehension. Even the very attempt to attack or reduce self-clinging might

very well be indeed an expression of egocentrism, if the motive is limited to

self-interest. Facing the dilemma of an invisible enemy who is possibly lurking

behind one's every move, it amounts to an almost impossible task! Thanks to the

wisdom insight of Machig Labdron, the root of self-clinging has been singled

out to be the body. Once this is made clear, and the body being a concrete object,

the remaining task is much simpler, though not easier.

According

to the wisdom insight of Machig Labdron, the real demons are everything that

hinders the attainment of liberation. Keeping this wisdom insight in mind, on

one hand, all judgments based on personal preferences and interests should be

given up, and on the other hand, all obstacles and adversaries could be

transformed by one's efforts into helping hands on the path toward liberation.

For example, a gain could be a hindrance to liberation if one is attached to

it, while an injury could be a help to liberation if one uses it to practice

tolerance, forgiveness and compassion.

Applying

this wisdom insight to the root of self-clinging, the body, Machig Labdron

formulated the visualization of Chod, and thereby transformed the root of

hindrance into the tool for attaining compassion and liberation.

C.

Impermanence and Complete Renunciation

The

body is the very foundation of our physical existence. Even after it has been

recognized to be the root of self-clinging, it is still very difficult to see

how to treat it to bring about spiritual transcendence and liberation.

Destroying the body would certainly end the possibility of further spiritual

advancement in this life but not necessarily the self-clinging. The fact that

beings are transmigrating from life to life attests to this. Ascetic practices

may temporarily check the grip of physical desires over spiritual clarity and

purity, but transcendence depending on physical abuse can hardly be accepted as

genuine liberation. The Buddha had clearly taught that the right path is the

middle one away from the extremes of asceticism and hedonism.

A

fundamental and common approach of Buddhist teachings is to remind everyone of

the fact of Impermanence. All things are in constant changes, even though some

changes are not readily recognizable. The change from being alive to dead could

occur at any moment and could happen in just an instant. Keeping impermanence

in mind, one can clearly see that all our attachments to the body are based

primarily on wishful thinking. To be ready for and able to transcend the events

of life and death one needs to see in advance that all worldly possessions,

including the body, will be lost sooner or later. Hence, a determination to

renounce all worldly possessions is the first step toward spiritual awakening

and liberation. Chod as a Buddhist practice is also based on such awareness of

impermanence and complete renunciation. In fact, many Chodpas adopt not just

the ritual practice but also a way of life that exemplifies such awakening.

Many Chodpas are devout beggars or wondering yogis who stay only in cemeteries

or desolate places and do not stay in one place for more than seven consecutive

days.

The

offering of the body through visualization in a Chod ritual is an ingenious way

to counter our usual attitude toward the body; instead of possession,

attachment, and tender, loving care, the ritual offers new perspectives as to

what could happen to the body as a physical object and thereby reduces the

practitioners' fixation with the body, enlarge their perspectives, and help

them to appreciate the position of the body on the cosmic scale. Chodpas would

fully realize that the body is also impermanent, become free from attachment to

it, and ready to renounce it when the time comes. When one is ready to renounce

even the body, the rest of the worldly possessions and affairs are no longer of

vital concern, only then can one make steadfast advancement on the quest for

Enlightenment.

D.

Bodhicitta

Machig

Labdron emphasizes that the offering of the body in Chod practice is an act of

great compassion for all beings, especially toward the practitioner's creditors

and enemies. Great compassion knows no partiality, hence the distinction of

friends and foes, or relatives and strangers does not apply. Great compassion

transcends all attachments to the self, hence all one's possessions, including

the body, may be offered to benefit others. In every act of visualized offering

of the bodily parts, the practitioner is converting an unquestioned attachment

into an awakened determination to sacrifice the self for the benefit of all. In

short, this is the ultimate exercise in contemplating complete self-sacrifice

for achieving an altruistic goal.

Chod

is a practice that kills two birds with one stone. On one hand, the attachment

to the body and self would be reduced through the visualized activity of

dismemberment; on the other hand, the visualized practice of satisfying all

beings, especially one's creditors and enemies, through the ultimate and

complete sacrifice of one's body would nurture one's great compassion. When the

attachment is weakened, the wisdom of non-self would gradually reveal itself.

Consequently, Chod develops wisdom and compassion simultaneously in one

practice; or to put it in another way, Chod is a practice that nurtures the

unification of wisdom and compassion.

In

Buddhism "Bodhicitta" refers to the ultimate unification of wisdom

and compassion, the Enlightenment, and to the aspiration of achieving it.

Therefore, we may say that Chod stems from the Bodhicitta of Machig Labdron,

guides practitioners who are with Bodhicitta through the enactment of

Bodhicitta, and would mature them for the attainment of Bodhicitta.

Only

when one is completely devoted to the service of all sentient beings can one

gain complete liberation from self-centeredness. Just as a headlong plunge

takes a diver off the board, complete devotion to Dharma and complete

attainment of liberation happens simultaneously. Only when considerations

involving oneself is eradicated, will an act in the name of the Dharma become

indeed an act of Bodhicitta, of Enlightenment. Developing Bodhicitta in place

of self-centeredness is the effective and indispensable approach to liberation

from self, and Chod is the epitome of this approach.

E.

Meditation Stability and Visualization

The

visualization practice of Chod is not an act of imagination. Were it just

imagining things in one's mind, there is no guarantee that such practice would

not drive one insane. To practice Chod properly one should have some attainment

of meditation stability so that the visualizations are focused and not mixed

with delusive and scattered thoughts or mental images. Indeed, Chod should be

practiced as akin to meditation in action.

To

be free from attachments to the body, we have seen above that destroying or

abusing it would not do. It is the great ingenuity of Machig Labdron to

recognize that attachments being mental tendencies can be properly corrected by

mental adjustments. Visualizations performed by practitioners with meditation

stability could have the same or even stronger effects as real occurrences.

Furthermore, visualizations can be repeated over and over again to gradually

overcome propensities until their extinction.

Using

visualization in Chod practices the body remains intact and serves as a good

foundation for the practitioner's advancement on the path to Enlightenment,

while the attachment to the body and all attachments stemming from it are being

chopped down piece by piece.

Visualizations

performed in meditation stability is a valid way of communication with the

consciousness of beings who are without corporeal existence. Hence Chod

visualizations as performed by adepts are real encounters of the supernatural

kind. They could yield miraculous results such as healing of certain ailments

or mental disorders that are caused by ghosts or evil spirits, and exorcism

that restores peace to a haunted place.

The

five essential ingredients as stated and explained above constitute the key to

the formulation of Chod as a Buddhist tantric practice. A thorough

understanding of the significance of these essentials is both a prerequisite to

and a fruit of successful Chod practices.

3.

The Benefits of Chod Practice

Enlightenment

is of course the ultimate goal of Chod practice. Machig Labdron revealed her

vast spiritual experiences by indicating signs of various stages of realization

in Chod. These teachings are still well preserved in Chod traditions. Through

the References listed at the end of this work serious readers may find some of

these teachings.

In

addition to the fruits of realization as indicated above and the application of

spiritual power to healing and exorcism as mentioned earlier, there are other

benefits that may be derived from Chod practice. Chod practice can help booster

the courage and determination to devote one's whole being to practice, beyond

considerations of physical well-being and life, thereby achieving complete

renunciation and significant realization. Chod practice could help total

removal of subconscious hindrances that are most difficult to become aware of

because these would surface only when challenged by grave situations like

dismemberment.

In a

dream state I sensed the relaxing effect of Chod; those joints of my body that

were tense became relaxed when a curved knife cut through them. The tension in

our mind is enhanced by our underlying concept of the body. By removing the

mental image of the body through Chod the tension is reduced. The natural state

of one's body exists before the arising of concepts, and hence, to return to it

one needs to transcend the grip of conceptuality.

Many

kinds of death are horrible to normal thinking; through practicing Chod it is

possible to go beyond attachment to physical existence, and have enough

spiritual experiences to understand that whatever the manner of death may be

they are just different ways to exit from the physical existence. Such a broad

perspective would enable one to remain serene in facing unthinkable tragedies.

Such an understanding would make it easier to tolerate, forgive and forgo

vengeance.

4. Dispelling

Misconceptions about Chod

A

fundamental rule of conduct of tantric Buddhism is the proper caring of, though

not attachment to, the body. In tantric Buddhism the ritual of Burned Scars of

Sila Commitment and the offering of burned fingers are not practiced. Most

tantric practices transfer one's preoccupation with the body by visualization

of the wisdom body of one's Yidam. In Chod the visualization and identification

with the black Vajra Yogini is important, but emphasis is on the visualization

of cutting and offering the body. The dismemberment is done in visualization

only, hence there is no infringement of the rule of conduct.

In

tantric practices the body is usually "meditated away" by returning

it in visualization to its empty nature of formlessness. Chod differs from the

rest by cutting it away for the compassionate cause of satisfying others'

needs. Chod should not therefore be considered as a practice contrary to the

rest. As far as the body is concerned, either approach depends on and makes use

of the conditional nature of the body.

The

activities visualized in Chod may seem like outbursts of anger, hatred or other

negative mentalities or barbaric drives. Indeed the dismemberment visualized in

Chod is not intended as a redirection or outlet for any negative impulse or

drive. Nor would it result in habitual actions that are negative or barbaric

because the visualizations are clearly understood to be born of compassion and

there is no bodily enactment that imitates the visualizations. To a Chodpa

these visualized activities represent determinations to destroy the illusion of

a permanent body which exists in concepts only. In the motivation of Chod there

is not even the faintest trace of a wanton disregard for life and the body. The

coolness to see and use the body as an object without reference to self is a

display of wisdom, while the intention to satisfy all others' needs is born of

great compassion. We should not commit the fallacy of deducing intention from

behavior because similar behaviors may have originated from diverse motives.

Nor should we be confined by considerations involving appearances into

submission to the tyranny of taboos; the liberation of employing whatever means

that seems appropriate is a true mark of wisdom.

The

dismemberment visualizations of Chod are opposite to morbid obsession with

cruelty, sadism, self-mortification, masochism and suicidal mania. Obsession

with cruelty, sadism, self-mortification, masochism and suicidal mania are

results of self-centeredness or its consequential inability to appreciate the

vast openness of the world and what life could offer for the better. Chod works

directly toward the reduction of self-centeredness. Chod and the rest may

appear to have similar elements, but they are squarely opposite in motivation,

mentality during practice, and the consequential results.

The

dismemberment visualizations would seem gruesome from an ordinary point of

view; however, from the point of view of things as they are and life as it is,

there is nothing frightful in what could have happened, nor in what had

happened. It is very important to appreciate the openness of mind that Chod visualizations

may lead to. In this respect Chod may be compared to inoculation.

The

black Wisdom Yogini is a manifestation of the wisdom of selflessness. Her

appearance may seem peculiar to people who have not been initiated into her

secret teachings, but the reader should be assured that every aspect of her

appearance signifies a certain aspect of the wisdom and compassion of

Enlightenment. This remark is to dispel shallow mislabeling of Chod as a kind

of demonic worship.

Actually

none of the misunderstandings discussed above would occur to a Buddhist

practitioner who has undergone the preliminary practices and possesses a proper

understanding of the philosophy and significance of Chod. However, such

misunderstandings would readily occur to most people who happens to come across

Chod rituals. Therefore, I think it advantageous to bring them out for

discussion so that they would be put to rest once for all.

Chod

is an antidote to grasping of the body and the self, but not a method to

increase antagonism. The basic spirit of Chod is not to destroy, conquer or

become an enemy of creditors, evil spirits, etc. Its essence is self-sacrifice

out of compassion and wisdom. Chod is an antidotal practice; a Chodpa should

not thereby become over concerned with the body in the opposite direction, e.

g., feeling aversion toward the body. The ideal result should be freedom from

preoccupation with the body and the self.

Chod

is an extreme practice. It is not the only path toward liberation from self,

but it is a valid path toward liberation. Without such understanding one's

knowledge of what it means to be liberated from the self is incomplete and

possibly erroneous.

III. Yogi Chen's Ritual of Chod

The

Sadhana of Almsgiving the Body to Dispel

Demonic Hindrance, Karmic Creditors, Attachment

to Self and the Concept of the Body

written

in Chinese by

the Buddhist Yogi C. M. Chen

translated

by his disciple

Dr. Yutang Lin

1.

Brief Introduction

From

Lama Gensang Zecheng I received "Great Perfection Pinnacle Wisdom,"

and from Dharma teacher Rev. Yan Ding I received the oral instruction on the

text and commentary of the preliminary practice of this practice, which I had

written down. The Gushali (Kusali) Accumulation, i.e., the practice of

almsgiving of the body, contained therein consists of only eighteen sentences.

The supreme practice of this method belongs to the Jiulangba (Chodpa) Lineage

which has been transmitted from Maji Nozhun (Machig Labdron; the

transliteration is in accordance with Guru Chen's pronunciation) down to the

present day. The practitioners of this lineage do not practice other sadhanas

but concentrate on this practice, and many attained realizations. This practice

can dispel the concept of the body, cut through the attachment to self, and

ward off hindrance caused by Karmic creditors, thereby enabling a

straightforward advancement on the Great Path toward Bodhi. I searched for this

teaching, but due to the absence of an Tibetan-Chinese interpreter, I failed to

translate the root tantra of this teaching. Consequently, based on the eighteen

sentences on Gushali which constitute one of the six preliminary practices of

Great Perfection, I expand the sequence and write down this work.

2.

Main Text

(1) Motivation

May all sentient

beings, who are limitless, like space, in number and are like mother to me,

possess pure and joyful body, and the causes resulting in such a body!

May all sentient

beings, who are limitless, like space, in number and are like mother to me, be

free from impure and tormenting body, and the causes resulting in such a body!

May all sentient

beings, who are limitless, like space, in number and are like mother to me, be

inseparable from Great Pleasure Wisdom Non-death Rainbow Body!

May all sentient

beings, who are limitless, like space, in number and are like mother to me,

stay far away from distinguishing friends and foes, relatives and enemies, and

abide in the equanimity of the Great Essential Body!

(2) Contemplation on Impermanence

Visualize

that all Karmic creditors, from present and past lives, of oneself and others

in the cemetery, appear and gather in front, simultaneously become keenly aware

of impermanence, and preach Dharma to them. Then recite the following stanza

with the accompaniment of bell and drum, chanting in a slow tempo.

All those

present and gather here have a sorrowful body;

Our sufferings are rooted in dependence on the body.

All things are originally pure, without a polluted body;

Defilement is piled up by one owing to this ignorance.

Possessing an impure body causes grasping of it as a castle of self;

Benefiting oneself and annoying others, all faults are thus accomplished.

Mind having grasped at this body, the body is no longer light;

Piling layers upon layers of impurity, the coarse five elements are

formed.

Coarse wind drifts and flows, with ignorance riding on this trend;

Like a horse out of control, the five poisons are ever winding.

The body leads to greedy love, such love leads to seven sorts of

emotions;

The body leads to ignorance or anger, these are also causes for downfall.

Killing and Robbing are mainly committed by hand, leading to sexual misconduct

are the eyes;

How many sinful deeds are committed by voice from the mouth!

Empty stomach and dried intestines, frostbite and cracked skin,

Unbearable hunger and cold are followed by misdeeds.

Eating salty dried animal corpse, wearing materials woven by silkworms,

Tramping on insects while walking, how many lives have we damaged?

When heavy and coarse five poisons pervade, anger and killing cause the

downfall into hell;

The body will be broken into pieces and then revive instantly to repeat the

punishment, no break for such sins!

Leprosy and cholera are born from greed in food and sex;

Crippled legs, cramped hands and venereal diseases may thus gather in the

body.

Followers of other religions practice with attachment to the body, and hence

cannot transcend samsara;

The wrong view of a self leads to ascetic practice of vainly covering the body

with ashes.

Variation in Karma of the three realms is dependent on the coarseness of their

bodies;

Formless realm is free from the body and yet still bound by the confines of

space.

To pursue clothing and food for the body, family members fight against one

another;

Distinguishing friends and foes, families and countries, the world is full of

wars.

Heavenly bodies suffer five defects, human beings may die young suddenly;

Having tiny neck but huge stomach, hungry ghosts are even more pitiful.

The strong preying on the weak, bows and arrows, nets and traps,

Knives and cutting boards, pans and pots, the sorrow of animal bodies are

multiple.

Eight freezing and eight sizzling hells, lasting for many kalpas,

Suffering without a break, the body is restored as soon as it is in

pieces!

Sinful deeds are committed by the body, consequences are also received by the

body;

In transmigration beings are preying on others who were their children in past

lives, without realizing this fact.

Just considering the debts and hostility of this life, when can they be paid

off?

Understanding that the grasping mind is without substance, we attain

equanimity.

(3) Visualization of Impure and Pure

Bodies

Visualize

in the impure body a white wisdom drop, the size of a pea, situated within the

medium channel at the center of the heart chakra. This wisdom drop gathers all

wisdom wind and the pure six elements—the constituents of all Buddha bodies,

the essence of life and merits without remains; the rest of the body is impure.

Yell "Pei" (Phat) once to eject this wisdom drop upward through the

Gate of Rebirth in Pureland at the top of the head. Visualize that this wisdom

drop transforms into the black Hai Mu (Dorje Pagmo) whose appearance is just as

described in the Sadhana of Hai Mu.

Abide

in the Samadhi of All-in-One, a Hua-Yen (Avatamsaka) Mystic Gate, and visualize

that the sinful Karma, sickness, hindrance, and evil disturbance of all

sentient beings in the three realms are gathering into the impure body left

below. All beings, including oneself, who have been persecuted by Karmic

creditors and enemies, merge into this body and are ready to be offered.

(4) Transformation of Impurity through

Offering

A.

At first visualize the usual offering of five kinds of meat and five kinds of

nectar in a skull cup. Recite these six words: Lang, Yang, Kang, Weng, A, Hong,

and simultaneously visualize according to their respective meanings of fire,

wind, space, increase, purify and transform.

B.

Then visualize in accordance with the following stanza. At the beginning of

each sentence yell "

The thick forest

of delusions, the self grasped by other religions, chop off the head, contain

the offerings to be rid of heavenly demons.

The sinful Karma

of the five-limb body, accumulated from killing and erotic behavior, mince it

to pieces and powder, thereby all grievances are forgiven.

The five organs

and six intestines, the thirty-six impurities, chop them into pieces and

stripes, the demons of Death and Aggregates are eliminated.

Leprosy and

malignant poisons, all sorts of contagious germs, transformed into nectar, what

can the Demon of Disease employ?

Sinful speeches

are issued from the tongue, throat and windpipe, chop them off and offer them

to Buddha, grudge and animosity are thereby released.

Delusions and

scattered thoughts, all Karmic winds, join the air to blow up the fire, after

the offering all are relinquished.

Mental Karma of

greed, anger and ignorance, most are rooted in the sexual organs, chop it off

and transform it into offering, enemies of jealousy are forever pulverized.

Six imbalances

of fire and water elements, transformed into the soup in the skull cup, or help

the cooking fire, they will not run wild from now on!

(5) Bless the Offerings

A. Recite in the usual fashion,

"Lang, Yang, Kang" and consider the fire of desires and the wind of

Karma transform into those of wisdom, and the skull of the impure body merge

into the huge skull cup visualized earlier, and all delusions also merge into

the skull cup. Recite as usual, "Weng, A, Hong" and consider all

parts of the body that have been chopped off are thereby transformed from scant

to abundance, from impure to pure, and from Karmic to transcendental; then all

these merge into a boundless ocean of nectar for limitless offering.

B. Recite the following stanza and visualize accordingly:

The supreme

blessing, like a shadow without substance, beyond awareness and intention,

light of equanimity pervades.

(Abide in

the Mahamudra Samadhi of Wisdom Light) The secret blessing, the A-Han (Ewam)

joy of the Yidam, proper and improper sexual behaviors, all are full of wisdom

drops.

(Abide in the Embrace Union Samadhi of Bliss Sunyata. All worldly and

transcendental beings merge with the Yidam parents, thereby even beings

engaging in wrong sexual behaviors are blessed and offer their wisdom drops.)

The inner

blessing, Maha Yoga, the Great Harmony, killing in itself or as means, killing

indiscriminately, the meat is piling up.

(Abide in

the Great Subduing Samadhi of Mahakala. Killing all evil, demonic beings and

yet transfer their consciousness into Yidam bodies, and their corpses are added

into the ocean of nectar for offering.)

The outer

blessing, all sorts of red and white delicacies, pure without pollution, all

inclusive without omission.

(Abide in

the Pervading Heaven-and-Earth Samadhi of Great Offering. Abide in the

incomprehensible Mystic Gate of Mutual Complementary of Visible and Invisible;

all meat and vegetables in the world, of men or heaven, become offerings

without interfering one another.)

(6) Formal Offering and Almsgiving

A.

First make offerings to the Gurus, Yidams, Dakinis, Protectors, etc.

B.

Then make almsgiving to all grudgers and creditors of oneself and others in

present and past lives, fulfill their appetites so that they are all very

pleased and become Dharma protectors, no longer causing obstacles. After the

almsgiving of nectar, offer them Buddhist teachings, at least recite the Heart

Sutra once and the Mantra of Releasing Grievances seven times, or recite, in

addition, other sutras, mantras or stanzas to instill wisdom and compassion.

The details are omitted (by the author, but not the translator) here.

(7) Participation in Realization

Eat

and drink the food offerings that are displayed in the Mandala; visualize

oneself as the Yidam and recite the following stanza:

Like gold in

ore, once purified would not be ore again, majestic and magnificent, the vajra

body is holy and pure.

Tummo needs no clothing, nectar needs no food, partaking food on behalf of all

beings, there is neither gain nor loss.

Karmic winds are exhausted, scattered thoughts no longer arise, abiding in

right thoughts, Dharmakaya is as indestructible as diamond.

Lion king entering the forest, pacing at will without fear, in contact with

five poisons, the four demons dare not confront.

Wisdom body with wisdom eyes, seeing without duality, no trace of self, neither

intention nor mistake.

Abiding in the equanimity of friends and foes, renouncing all love and hatred,

the great compassion of same entity, turning all connections into enlightening

activities.

Great enjoyment of wisdom, the sublime joy offered by Dakinis, the precious

youthful vase body, supreme joy everlasting.

Pure body with all channels open, supernatural transformations occur without

limit, fulfill completely all wishes, salvation of all beings that ends

samsara!

Inconspicuously, as the Eternal Silent Light; conspicuously, as the wondrous

rainbow; completing with the eight merits, it is the treasure of all

Enlightenment.

Free from preconception and live in ease, without the body yet the great self

remains, as long as there are beings remain in samsara, that would be the

reason for my non-death.

(8) Dedication of Merits

Seer and hearer,

ridiculer and accuser, when being thought of, they all become liberated.

From the impure body transform into wisdom body; eternal, joyful, free and

pure, all attain Buddha's five bodies.

In

the years of the Republic of China, Ji Chou (year), First month, the fourth day

(i.e., Feb. 1, 1949), on the occasion of the auspicious birthday of the Maha

Siddha of Non-death, Dangtong Jiapo (Thangtong Gyalpo), and the auspicious date

of Holy Mind Green Dragon, composed in the retreat room in the Burmese Buddhist

Monastery on the Vulture Peak in India.

Translated

on May 8, 1996

IV. Chod in

the Light of Limitless-Oneness

Chod was named by its founder Machig Labdron as the Chod of Mahamudra. This

indicates that the goal and function of this practice is nothing other than

achieving Full Enlightenment. Enlightenment may be characterized in various

ways to help people appreciate the value of working toward it and understand

the principles underlying practices leading toward it. In recent years I have

chosen to characterize Enlightenment as Limitless-Oneness which is originally

pure. For a detailed exposition please read the first two chapters of my book "The

Sixfold Sublimation in Limitless-Oneness" which is available for free

distribution.

In

the light of Enlightenment as Limitless-Oneness, the fundamental guiding

principle of all Buddhist practices may be liken to a sword of liberation with

two blades; one side is Opening Up, and the other side is No Attachment. The

function of each Buddhist practice may be understood through these two aspects.

As to advanced practices that emphasize non-duality as the approach, or

refinement of all practices through non-duality in Sunyata meditation, one simply

needs to remember that both blades are of the same sword.

In

Limitless-Oneness all notions of a self are extinguished by limitlessness. No

attachment in this indescribable state features two aspects: On one hand, it is

the growing out of all kinds of attachments, like a man free from the

importance of childhood toys; on the other hand, it is freedom from the

self-deceit that one could judge or control others. With full awareness of the

selfless and conditional nature of all things, one would not interfere in

others' ways but become liberated in such open-mindedness. Only thorough

understanding of the conditional nature of all things could one help shape a

sensible and tolerant outlook on life. The significance of this remark would

become more obvious if one looks at ways of life that are guided by fanatic and

dogmatic beliefs.

Limitless-Oneness

implies, on one hand, the oneness of different aspects such as all aspects of

Buddhahood, all aspects of samsara, etc., and on the other hand, the oneness of

opposites such as good and evil, wisdom and ignorance, compassion and cruelty,

etc. Both kinds of oneness would seem either confusing or impossible from the

normal logical point of view. Therefore, its transcendental purport will be

carefully explained below.

Limitless-Oneness

is the originally pure state that a Buddha became awaken to at the moment of

Enlightenment, i.e., the complete and final emergence from engulfment in

worldly life. In such a state all distinctions are harmonized in their original

purity and oneness. Such oneness can be experienced but cannot be described.

Such oneness is beyond the understanding of beings who are still dominated by

worldly considerations and know only to grasp on transient distinctions. In

such oneness the distinctions are still recognizable and yet simultaneously

undifferentiable. Please consider the analogy of a loving mother who can

distinguish all her children and yet could not make any distinction in her love

toward them.

The

Limitless-Oneness of opposites, such as good and evil, wisdom and ignorance,

compassion and cruelty, etc., could be understood in an additional light. These

opposites are in oneness in the sense that they are like two ends of the same

street, the street being the conditional nature of all things. The conditions

may be pulling and pushing toward one end or the other and resulting in extreme

opposites, but both ends are similar as results determined solely by the

combination of conditions. Once this conditional nature of opposites is

understood, what is the justification for us to be proud of our goodness, to

blame others for their evil activities, or to hold our goodness in antagonism

against others' evil activities? With a switch in the circumstances, they could

have been in our position and we theirs. Lacking such understanding often

results in shallow displays of moral indignation and condemnation. One who sees

deeply into the conditional nature of opposites could not help but have

sympathy and compassion for all the fightings of opposites in life. Without

such insight how could anyone forgive and forbear all the wrong doings in the

world, and persist in the pure pursuit of Enlightenment?

In

the light of Limitless-Oneness the usual distinction and antagonism of

opposites would become meaningless. The one and only essential task would

become the awakening of all beings to Limitless-Oneness because that is the

ultimate and true solution to all problems and sufferings in samsara. Machig

Labdron's teaching that the real demons are everything that hinders the

attainment of liberation obviously stems from this transcendental and panoramic

perspective. Furthermore, any method that is conducive to this transcendental

awareness could be employed under suitable guidance by experienced teachers.

Therefore, the dismemberment visualizations and the inhabitation at desolate

places by Chodpas should be understood in this light and be respected for its

transcendental significance. Just as the activities of surgeons and coroners

are service to mankind, the visualizations of Chodpas are service to beings at

the spiritual level.

Although

the object of visualized cutting is the body of the practicing Chodpa, it has

been identified through visualization with all things in the Buddhist cosmos.

Such an identification may seem absurd from the ordinary point of view;

nevertheless, it is not a delusive act of imagination or self-deceit. Such an

identification is possible only in the light of Limitless-Oneness, and it is

meaningful because all things lack self nature, and when the illusion of a self

is cleared away, they are experienced to be originally in oneness. Indeed, a

Chodpa must understand the philosophy of Limitless-Oneness, of the unity of

Dharmadhatu and the selfless nature of all things, in order to practice properly.

Through such universal identification in visualization a Chodpa would gradually

gain insight and experiences in the realization of Limitless-Oneness.

The

main obstacle to realization of Limitless-Oneness is self-clinging. The main

purpose of Chod visualizations is to reduce and eradicate self-clinging that is

rooted in identification with the body. Hence Chod is a fundamental approach

that works directly at the root of the hindrance, and its result would no doubt

be a direct experience of Limitless-Oneness when the identification with the

body is cut away. This is the reason why Machig Labdron characterized her

teachings as the Chod of Mahamudra, thereby indicating that it is for the

attainment of Dharmakaya.

The

identification of a Chodpa's consciousness with the black Vajra Yogini should

also be appreciated in the light of Limitless-Oneness. Vajra Yogini is a wisdom

being meaning that she is a manifestation of the ultimate Limitless-Oneness.

Through this manifestation all enlightened beings are represented, and all

their wisdom, compassion and blessings are gathered. The practicing Chodpa is

no longer an ordinary sentient being but the representative of all enlightened

beings. Consequently all the visualized activities cannot have any connection

with the self but aim only at the salvation of all beings in samsara. In modern

terms, the Vajra Yogini serves as a role model for Chodpas, and in general,

Yidams are transcendental role models for tantric practitioners.

In

Limitless-Oneness spatial and temporal references would loose significance,

consequently the salvation activities are unbounded by spatial and temporal

considerations and limits. This is by no means fanciful talks only.

Supernatural events and abilities that transcend the normal spatial/temporal

limitations are abundant. The practice of Chod, indeed of any Buddhist

teaching, should be undertaken in full accordance with such understanding. The

practitioner should possess a firm conviction that the practice does affect the

salvation of all beings everywhere for all eternity.

The

transcendence of Buddhist practices over spatial and temporal limitations also

implies the carrying over of Buddhist insight gained through practices into

daily life. Chod practiced in the light of Limitless-Oneness would free one

from worldly considerations and thereby enable one to see clearly what is of

real significance in life and make wise decisions in daily life. Furthermore,

Buddhist practices would last a whole life for devout practitioners and there

are even practices for the dying process and the Bardo (intermediate) state

between death and the next life. A Chodpa could practice the identification

with the black Vajra Yogini during the dying process or the Bardo state and

thereby transcend ordinary death. When the identification is achieved, the

dismemberment practice would then become the first act of universal salvation

for this enlightened being.

The

non-dual state of selflessness is emphasized by all Buddhist practices as the

ultimate goal and achievement. No Buddhist practice is authentic without

sublimation through meditation of non-duality. Chod practiced in the light of

Limitless-Oneness is a direct attempt to realize non-duality. It is a practice

of non-dual activities, or of non-duality in action. Even though Chod

visualizations involve the cutter, the knife and the body dismembered, all of

them are cooperating as a team in achieving freedom from superficial duality.

Non-duality should not be synonymous to non-distinctions and non-activities.

Were they synonymous, why not simply use "dead" instead? Non-duality

is truly realized only when the bondage of attachment to appearances is

dismembered. When the servitude of submission to formality and appearance ends,

non-duality is everywhere all the time, alive and active in a natural way.

What

is the difference between one action as performed by a Buddha and a similar

action as done by an ordinary person? If the actions could be isolated, taken

out of their contexts, then on the scale of the universe there would probably

be no noticeable difference. Nevertheless, a fundamental difference does exist

in that each action of an ordinary person is somehow connected to

self-centeredness and limited by spatial and temporal connections and

considerations, whereas each action of a Buddha is an opportune expression of

the wisdom and compassion stemming from Limitless-Oneness. Any Buddhist

practice, including Chod, should be an attempt to channel all mental and

physical activities into Limitless-Oneness. A Buddhist practitioner should

practice with the intention to imbue the openness of Limitless-Oneness into all

one's thoughts, emotions and activities.

Why

is Chod a practice that can be taught to novices as a preliminary practice and

yet is also characterized as a practice aiming at the highest achievement of

Enlightenment? In the light of Limitless-Oneness the answer is forthcoming. In

Chod there is a tangible object to work with, namely the body in visualization.

Hence it can be taught to novices as a preliminary practice, and as such its

main function is the accumulation of merits through almsgiving and the

reduction of bad karma through paying back to creditors and enemies. As a

Chodpa gradually understands better and better the philosophy of

Limitless-Oneness and gains more and more insight and realization through

accumulation of Chod practices, Chod gradually displays its intended function

and power as a direct attack to the self-clinging rooted in attachment to the

body. In other words, as a Chodpa expands gradually into Limitless-Oneness

through Chod practices, Chod is simultaneously sublimated from a superficial

enactment of imagined activities into an experience of Limitless-Oneness in

action.

In

the light of Limitless-Oneness the transient nature of one's physical existence

becomes obvious. In fact, one's physical existence could end at any moment.

This is no reason for despair because one's wisdom and compassion could take

shape through activities that would have influence everywhere forever.

Furthermore, the transient nature of our physical existence, once fully

understood, could help us become free from self-centeredness; it would then

become easier to give up preoccupation with something that cannot be kept for

good. One could then even sense the common fate of living beings, the fear, the

dangers, the struggles and the sufferings of life, and awake to the compassion

that encompasses all beings in oneness. The conditional nature of all things

would dictate the continuation of samsara with its many pitfalls. Nevertheless,

the compassion born of Limitless-Oneness also commands unceasing enlightened

activities of salvation. Dedicating one's life to the service of the

cultivation of all beings' Enlightenment becomes a deliberate choice and act of

will that illustrates the transcendence of Bodhicitta, the unification of

wisdom and compassion, over transient human existence. One who lives a life of

Dharma service would enjoy what life could offer best. Chod practiced in the

light of Limitless-Oneness becomes natural and meaningful; without the

illumination of Limitless-Oneness Chod could become a bloody struggle with the

self that even further tightens the bound of self-consciousness.

V. Reflections on Chod

Through my Dharma practices I gradually become less concerned with myself and

begin to attempt to appreciate the limitless perspective of Buddhas and

Bodhisattvas. The basic structure of Chod consists of the destruction of the

body and self, and identification with the black Vajra Yogini and her salvation

activities. The underlying message of this structure seems to convey the

following image: The great mother Machig, from her infinite compassion and

liberation, is looking down at all sentient beings suffering in samsara and

calling out: Do not be fooled by the body and its transient existence, cut

through attachment to it and all worldly considerations, become one with the

wisdom of selflessness and devote your life to salvation services!

Chod

is a universal practice in almsgiving because what is given away is in everyone's

possession, even a beggar can practice almsgiving in this way. However, Chod

amounts to the most difficult practice in almsgiving because what would be

given away, if the intention is taken seriously, is the body and that means one's

very existence. The extent of sacrifice that a Chod practice is hinting at

would be a challenge to one's sincerity in the practice of almsgiving.

Proper

caring of the physical body is emphasized by Tantra. However, there is also the

teaching that one should act with complete disregard for oneself in order to be

liberated and to best serve others. How could these contrary teachings be

balanced or even harmonized in practice? Under normal circumstances proper

caring of the body is adequate because it would enable one to perform and

continue Dharma practices and services. Nevertheless, there are also situations

when complete disregard for one's interests is needed in order to gain

enlightened realization or provide better compassionate service. For example,

very advanced tantric practitioners would live a life of spontaneity to realize

non-duality. Such a way of life takes neither one's health and life, nor social

norms and values into consideration. As recorded in the "Sutra of

Compassionate Flowers," Great Bodhisattvas had willingly given all their

possessions including bodily parts to satisfy sentient beings' wishes; their

intention is simply to set ultimate examples of compassionate services. Chod is

an ideal harmonization of these contrary teachings. On one hand, there is no

physical damages involved in the practice, and on the other hand,

self-sacrifice is practiced over and over again in visualization.

Viewing

the body as the aboard of this life, then the practice of Chod also implies

freedom from attachment to one's aboard, to one's native place, to one's

experiences good or bad, and to a sense of familiarity. It is difficult to

become free from attachments to all these; if one can observe oneself carefully

then it will become apparent that one is always reacting to one's past

experiences good or bad, and that one's activities are often tinted by the

shadow of past experiences. The aim of all Buddhist practices is the complete

emancipation from all bondages, and to achieve this goal a practitioner needs

to extend the implication of his practices to all aspects of daily life.

Therefore, the extension of implication as indicated above is of great

importance.

One

basic constituent of the notion of something that exists independently is that

it is there continuously without noticeable changes. In fact, all things change

in time and there is no such continuity; the only continuity that anything

might have is one's grasping to the concept of it, and, upon closer

examination, this grasping often turns out to be also impermanent. Most of the

time one's grasping to the body is simply a grasping to a vague mental concept

or image. Through the visualization of dismemberment Chod is mentally

destroying the spatial and temporal continuity of the imagery of one's body.

Hence, Chod is a practice to go beyond the grasping to the mental image of one's

body. Through Chod practices it is possible to reach the stage that is free

from this image.

Ma

Machig, as she is affectionately called by Tibetans, emphasizes that in Chod

the offerings should be given out of compassion. Through the offering of the

body in visualization the object of attachment is no longer there;

consequently, two effects are arrived at simultaneously: To the donor,

appreciation of both the wisdom of no attachment and the freedom from

attachment increase; whereas to the recipients, they lost the object of their

antagonism (envy, animosity, malice, fighting, etc.), and instead of merely

experiencing the non-existence of antagonism they are unexpectedly satisfied to

their hearts' content. Due to such generosity they might reflect and gain some

appreciation of Sunyata, especially the all encompassing aspect of it. How

compassionate and wise is Ma Machig to have bestowed on us such a wonderful

practice that all who are touched by it may grow in wisdom and compassion! This

is indeed the epitome of a gift of compassion.

Transforming

one's hindrances and weakness into helpful training grounds for advancement to

the goal is the essential strategy that enlivens the quest for Enlightenment.

Without such understanding and maneuvering the quest for Enlightenment could

easily be trapped by formality and stereotyped thinking into the snare of

dualistic antagonism, the very trap that one is trying to avoid. This is also

the reason why some advanced teachings in Buddhism would emphasize non-action

over purposeful activities. (Non-action in this context does not mean no

activities, but only no preconceived activities.) Through Chod the object of

fundamental attachment and delusion is not only reduced but also wisely

employed toward the development of compassion and Enlightenment. One could say

that the strategy of Chod is to transform attachment into useful compassionate

service; this is the marvelous wisdom of Ma Machig, the Dakini, and a special

feature of advanced tantric practices in general.

Chod

also provides an opportunity to face the moment of departure from this life,

even though it is only in visualization. At such a moment a reflection of one's

whole life would naturally arise; and one could not help but ask oneself about

what one has done with this life and what it all means. If all worldly

relations and possessions would abruptly become naught in the end, what better

choice does one have than to devote oneself to the everlasting Dharma service

and quest for Enlightenment? In the universal service of salvation through

propagation of Dharma, personal death no longer means the end of service or the

vacuousness of life. Since the moment of departure from this life is uncertain,

how could we keep procrastinating our Dharma practices and services? The

fragile nature of our health and vitality dictates that we engage in Dharma

practices and services now lest the opportunity of a lifetime would be lost.

Blood

relation is a basic bond of humanity, and it is based on the body. Hence, Chod

would be an effective practice to transcend considerations and biases that are

rooted in blood relations. Marital and sexual relations are related to the

body, therefore the liberating effect of Chod would also spread over to curtail

attachments rooted in such relations. Health and economic considerations are

rooted in the preservation of the body. Therefore, Chod would also affect the

grip of such worries. In short, all worldly considerations would be affected by

Chod. It is necessary to work toward clarity of mind that transcends these

relations and considerations in order to attain Enlightenment. However, this

does not mean that these relations and considerations are necessarily

hindrances to liberation. Transcendence does not mean indifference to nor

avoidance of these relations and considerations; indeed transcendence should

imply an impartial understanding of the nature of all these worldly relations

and considerations.

In

the traditions of Chod there are many rituals with varying visualizations as to

the manner of dismemberment and the principal and attending recipients invited.

Such details of visualization are important because they enhance the effects of

visualization. Besides, in the light of non-inherent-existence which implies

the futility of grasping at concepts, these details are all there is to the

practice.

Ma

Machig teaches that there are three ways to pronounce "Phat," the key

word used during a Chod practice, and each conveys respectively the intention

of calling, cutting through, and offering. On one hand, we should be grateful

for such teachings on fine discriminations in the usage of expressions; on the

other hand, this fine point illustrates the versatility of formal expressions and

the possibility of being misled by fixed interpretations of expressions.

The

offering of the body as visualized in Chod signifies complete offering of one's

worldly possessions, including one's life. In fact, the path for a spiritual

quest is often one of spiritual attainment through complete offering of one's

life and self. For example, in Christianity in order to provide a basis for

universal salvation Jesus made the dramatic and extreme sacrifice of knowingly

moving toward crucifixion. Even now the blessing of his sacrifice is conveyed

through the sacrament which uses bread and wine to symbolize the offering of

his body and blood. Eucharist as practiced in Catholic churches resembles in

spirit the dismemberment offering of Chod. In most cases one's spiritual quest

consists of lifelong cultivation of transcendence through spiritual practices

and services. Chod is quite suitable for lifelong cultivation of wisdom and

compassion.

When

one is preoccupied with minor things, one would lose sight of higher goals.

Engaging in disputes over minor points would prevent one from recognizing the