Buddhist Meditation

Systematic and Practical

CW35

Chapter IX

THE FOUR FOUNDATIONS OF

MINDFULNESS: A

A Talk by the Buddhist

Yogi

C. M. CHEN

Written Down by

REVEREND B. KANTIPALO

First Published in 1967

HOMAGE TO JE TSONG-KHAPA, THE FOUR AGAMAS,

AND THE FIVE HUNDRED ARHATS

Chapter IX

THE FOUR FOUNDATIONS OF MINDFULNESS:

A

Mr. Chen had heard of

the writer's intention to visit

Bhante remarked that the writer's notebook, quite a

thick one, was now near its end and Mr. Chen promised many more pages of notes

yet. "We are only on Chapter Nine," he said, "and there are at

least six or seven to follow."

A. The Homage

To begin

with, our homage is the same as in the last chapter, for the subject matter

here is also basically of the Hinayana, although we

shall see the correspondences with various doctrines of the Great and

B. Two Purposes for Samapatti

The positive

purpose is to attain enlightenment. This, however, is in the position of

consequence, so for us unenlightened worldlings there

is no need to talk much about it. We are in the position of cause, so for us

the negative purpose is the most important: that is, to rid ourselves of

obstacles. When this is done, positive results will automatically appear. I

have made a list to illustrate the hindrances:

Cause

|

Hindrances

|

|||

Five dull

drivers

|

Doubts

arising from the passions

|

Doubts

about practice

|

Egoism of

person

|

(klesavarana)

|

Five sharp

drivers

|

Doubts

about the truth

|

Doubts about

view

|

Egoism of dharmas

|

(Jneyavarana)

|

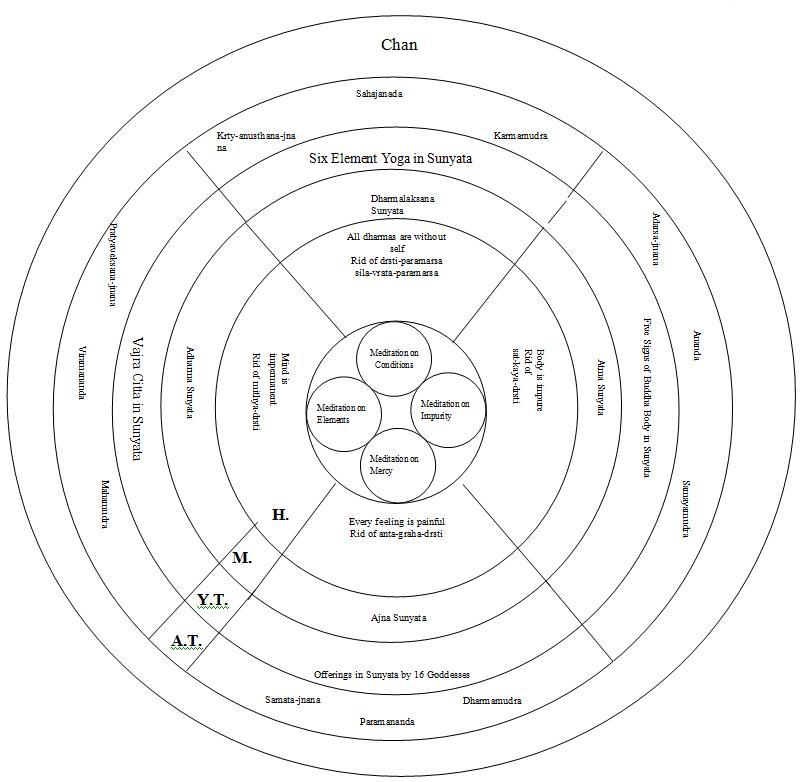

H.—Hinayana

M.—Mahayana

Y.T.—Yogic Tantra

A.T.—Anuttara Tantra

We have

already talked in the last chapter about the five poisons, or the five dull

drivers, as they are called here, which produce the klesavarana,

upon which the view of the personal ego is based. The first line of this list,

then, has been described. The second line will be the subject of this chapter,

where the samapatti of the four mindfulnesses will be the medicine prescribed for the five sharp drivers, the veil of

knowledge, and the attachment to the view that the dharmas have "ego." (See also the diagram showing the four mindfulness

meditations and their correspondences in the other yanas.)

The five

meditations of the last chapter and the four of this one are only to get rid of

these factors driving us on, the gross or dull ones and the more subtle sharp

ones. Although in both chapters only nine meditations are described, still they

are more or less sufficient to get rid of these hindrances, which is our

purpose, and we shall find upon examination that all the other meditations are

included in them.

C. A Notice on the Five Sharp Drivers

In the

1. Satkayadrsti—the view of

"my" of the body and not knowing that it is really a mixture of the

five aggregates (the skandhas—form, feeling, perception,

habitual tendencies, and consciousness). This is viewing what is merely a

changing continuity as being "really my body," and upon this,

building the further idea of "myself." Things which surround "my

body" are then thought of as "mine," whereas in fact there is no

owner of them. From the union of the ideas of "I" and

"mine" comes the false view of "myself."

2. Antagraha—extreme or one-sided views. Since most people at

first take hold of the ideas of "I" and "mine," so when

they come to think about death, their speculations veer to one of two extremes.

Either they suppose that after dying, they cease to exist (the view of

annihilation such as the communists and ordinary materialists), or they believe

that though the body has died, something subtle remains, some spirit, some soul

belonging to "me" somehow goes on (this is taught in all religions

except Buddhism). In this way, such people wander from one side to another,

lost among a maze of one-sided views.

3. Mithya—false view. This means not recognizing the law of

cause and effect (in Buddhism this is better called "dependent origination"

or "conditioned co-production"), which is the Buddha's teaching on

the operations of karma. If one thinks that actions produce no results, then

one may do evil without any fear and not expect any reward from doing good

actions. All these five sharp drivers are false views, but this one is the

falsest among them.

4. Drstiparamarsa—stubborn, perverted views, taking inferior

things as superior or vice versa. It is common enough to think that an

incorrect view is in fact correct. Having such a perverted view, one may then

perform evil actions, supposing that such actions are really wholesome.

The writer thought of

the Holy Inquisition when surely many priests sincerely believed that they were

saving souls by burning bodies.

Thus

perverted views are strengthened by wrong actions.

5. Sila-vrata-paramarsa—holding a false view regarding what is

forbidden. This is falsely and unreasonably considering some things as forbidden,

such as adhering only because of custom, convention, superstition, or blind

faith. For instance, a man may keep cows, regarding them as divine, or

chickens, believing that they are spirits. He does not eat their flesh, having

the view that, as a result, he may be born in heaven. Another example of

viewing a false cause as a real one is thinking that one may gain liberation by

nakedness, by smearing oneself with ashes, or fasting for a long time. These

are some examples of this sharp driver, whereby instead of heaven or

liberation, harm to oneself can be the only result. Very often people who have

firm faith in some false practice neglect the really wholesome spiritual

factors, such as renunciation, morality, etc.

All five of

these sharp drivers are corrupt knowledge and are not rooted out until one has

obtained the third path, that of insight (darsana-marga).

Neither the first (of accumulation) nor the second (of preparation) are

sufficient to dislodge the sharp drivers.

D. Why the Four Mindfulnesses Stress Elimination of the Five Sharp Drivers

1. These four

meditations contain the three Dharma-seals (tri-laksana: anitya, duhkha, anatman) and these distinguish Buddhism from other

religions. To realize them requires very fine meditations, as they are subtle

compared with the gross hindrances overcome in the last chapter. These three

seals are extremely important.

It is also

said that there are two forms of meditation: those within the three realms

(karma, rupa, arupavacara),

and those beyond them. It is our real purpose to practice the latter, for which

a thorough grounding in the four mindfulnesses will

be required. These four remove the sharp drivers and enable transcendental

meditation to be attained.

2. The five

dull drivers may be eliminated by the five meditations of the last chapter, so

that only the sharp drivers remain to be cured by the medicines offered here.

3. The most important of the four is the last, concerned with

the realization of the no-self of dharmas. Before we

can arrive at this, the other three must have been practiced, thus finally

removing the five sharp drivers.

E. The Practical Method of the Four Mindfulnesses

Two kinds of

method can be distinguished. In one, the practice of the four proceeds

separately; in the second, they are practiced together.

1. As Practiced Separately: The Practical Method

A stanza from

the Kosa says:

"Upon

what you have accomplished in samatha, base the

practice of the four mindfulnesses and (not only

practice them but) establish them firmly."

We should

draw the reader's attention to this: it is essential to understand the

importance of the foundations of mindfulness found in the preceding

meditations; also, one must understand that these meditations are subtler than

the former ones—there would be no need to practice them if they were not.

a. Samapatti of bodily impurity. I have classified this into

four kinds:

i.

The living body impurity of the thirty-six

parts, twelve of which are outside the body, twelve composing the body itself,

and twelve within:

Outside the Body

|

Of the Body Itself

|

Within the Body

|

hair

on the head

|

dead

outer skin

|

liver

|

hair

on the body

|

growing

inner skin

|

gall

bladder

|

nails

|

blood

|

bowels

|

teeth

|

flesh

|

stomach

|

dirt

found in the eyes

|

muscles

|

spleen

|

tears

|

nerves

|

kidneys

|

drool

|

bones

|

heart

|

spittle

|

marrow

|

lungs

|

excrement

|

fat

|

fresh

food receptacle

|

urine

|

lymph

|

partially digested food receptacle

|

grease

on the skin

|

brain

|

phlegm

of the lungs

|

sweat

|

membranes

|

nasal

mucous

|

We should

meditate on all of these. But it is not enough for us to try to find our

"self" in these impure matters; we should practice the other aspects

of this meditation.

ii. The

impurity of the dead body. This we have already discussed in the five

meditations and, from the impurity meditations there, we should have gained

both the will to renounce and the perception of impermanence.

iii. Impurity

of perverted views about the body. One has the idea of "my" body or

that this bodily contact "belongs to me." This means that ego is

extended to other bodies over which we consider that we possess proprietary

rights. We have ideas such as "my" wife, or, from the stimulus of

bodily contact in kissing, of "my" girl. If this meditation is

successful then the first of the sharp drivers (satkayadrsti)

will be converted.

iv. Incomplete

realization of impurity of the body. This refers to the partial realization of sunyata in the Hinayana when,

with a spiritual body, one "touches" nirvana. This view in the Lesser

Vehicle is incomplete, yet we shall soon see how to choose meditations from

among its practices to act as a bridge to the Mahayana.

For our

present consideration, the middle two are the most important, as the first has

been dealt with, while the fourth is yet to come.

But in this

chapter, for the sake of easy and tidy classification, we should make the four

foundations become five to fit in with the five sharp drivers. This can be done

without any distortion if breathing is considered as a

mindfulness in conjunction with all the other four. Thus in this

meditation, we breathe out, focusing our attention upon one of the thirty-six

objects, and then breathe in regarding its specially repulsive character:

breathing out, consider the hair on the head; breathing in, its greasiness, bad

smell, dirtiness, etc. In this way we proceed through all the thirty-six

objects one by one, breath by breath.

b. Every

Feeling is Painful

i. This

meditation is continuous in content from the merciful mind and having pity on

others. Therefore in the first stage of this meditation, one should think only

of the feeling of pain as mentioned in the Four Noble Truths.

ii. In

addition to the above stage, the meditator should

think: there are three kinds of feelings (pleasant, painful, and neither

pleasant nor painful) but if all these are perceived as painful, then we shall

recognize thoroughly that worldly pleasure ends with pain, and that the feeling

of neither is a kind of ignorance. As a result we make progress and enter sunyata.

iii.

Therefore, by taking others' painful feelings upon ourselves, we develop the Bodhi-heart. When we meditate on every feeling as sunyata, then spiritual and unchanging pleasure, the real

feelings of the Buddhas, arises.

iv. With more

progress, we come to the special pleasures of the Vajrayana,

which are enlarged sixteenfold in the third

initiation.

"We are talking

here of Dharma beyond the pure Hinayana tradition," reminded the yogi, "so it will

be helpful to understand these correspondences through our new diagram."

In

correspondence with breathing: on the exhalation consider the cause or object

of pain, and on the inhalation, the result of pain.

As pain and

pleasure are opposite and one-sided views arise concerning either, if one

meditates on them as empty, thus these views (antagraha)

are converted.

c. The mind is

impermanent. Of the mind in the past, nothing remains; it is already gone, and

even if you want to pursue it, this is impossible as nothing can be found.

Regarding the future mind, we have no idea what we shall think in time to come.

Where will these minds come from? What will be their objects of thought? At

present, no mind stays the same even for one moment; this has been the law in

the past, is certainly so now, and there is no reason to doubt that it will

continue so in the future. No real mind can be found which abides in any time.

Considering

the mind first as an entity, we cannot find anything to call permanent or

stable. If, on the other hand, we examine it under the three aspects of truth then:

i. Its essence

(a source of its continued working) cannot be found.

ii. We cannot

say of its quality whether it is red, green, round,

square, sharp, blunt, large, small, rough, or smooth; whether joyful or sad,

mind has no form.

iii. No

specific function can be discovered, since this varies from time to time. From

an angry mind, a person may act upon his anger. In this way people mind their

minds. But if we take no notice of the mind, if we just say "never

mind," then no function at all can be discerned.

We may also

examine the mind in relation to the breath. When breathing out, we take a

subject to investigate, and when breathing in, reach our conclusion upon it. On

the exhalation, we may ask ourselves a question such as "What is this

mind's function?" On the inhalation, give the answer: "No function

can be apprehended."

If there is

no mind at all, then the master of the perverse views (the "person"

holding them) has no source at all, hence the sharp driver called mithya is dealt with.

d. All dharmas are without self. There are many kinds of non-self

distinguished in the different schools of Buddhist thought.

i. One

particularly taught in the Hinayana is anatman as escape. Many similes teach escape from the false

idea of self and here we give five examples:

First: The

master is asleep in his house when it catches fire at midnight. He thinks,

"How shall I escape being burned alive?" Here the house is the self

and escaping from it means not being burned in the fire of passions.

Second: A

farmer whose ox has strayed away naturally wants to find out where it has gone.

Still searching at nightfall, he finds an ox which he thinks belongs to him,

but the next day discovers that it is the king's beast. Thinking, "I

should get rid of this ox, or I may be accused of theft," he releases the

animal and so escapes punishment. Here the ox is like the self mistakenly

regarded as real, and letting go of it, one escapes the punishment of continued

birth in samsara.

Third: This

concerns a child. A woman inside her house hears a child crying in the street.

Supposing it to be the sound of her own son, she runs out and brings the boy

inside. Then she sees her mistake. "This is not my own child; it must be

the neighbor's." So she quickly returns the boy

to the street and so avoids punishment. In the same way people mistake something

as belonging to them, as a "self," and should quickly give it up if

they do not wish to experience painful results.

Fourth: A

fisherman wants to catch a fish in a certain pool so he casts his net. After a

time, he feels that the net is very heavy and may break if he tries to draw it

out. He thinks, "I have a fine catch," and reaches down with his hand

into the net, taking from it a large snake. He knows immediately: "This is

very dangerous," and without more ado throws it away and escapes. In this way

we fish for a self and find out that all we catch is a great danger. We should

throw this away and escape.

Fifth: A man

takes a wife whom he did not know was a half-ghoul and lives with her for many

years. One night he wakes up to find his wife already leaving the house. He

follows her until they reach a cemetery where he sees her eating the flesh of a

corpse. He thinks to himself, "All these years I

had no idea she was a non-human being. If I return to live with her again, one

night she may feed on me." So he flees. For long we have identified

something as a self but coming to recognize the danger therein, we should flee

far away from such a false idea.

ii. Another

idea of dharmas as selfless is contained in the

doctrine of atoms or matter which cannot be split into anything finer. All

beings and objects possessed of form, whether gross or subtle, were, according

to this school, to be systematically analyzed into these atoms. Thus it was

said that in those beings or objects, no self existed, but on the other hand

these particles themselves were grasped at as though really existing. So while

the followers of this school (Sarvastivada) had a

means to rid themselves of ideas of the self, they

still hung on the concept of a multiple reality and thus their teaching of sunyata was incomplete.

iii. By the

process of analysis arriving at anatman. Two schools

used this method but disagreed as to the nature of dharmas.

The Sarvastivadins maintained anatman but taught also the existence of dharmas in the past,

present, and future. There is no self in any dharma, they taught, but they did

not examine the dharmas themselves to find out what

they are.

The second

school, Satyasiddhi, had the doctrine of the true

idea of sunyata, retaining the concept of atoms and

so arriving at their emptiness only by analysis.

In time as

well as matter, it was taught that indivisible particles existed. In both

cases, a residue of unbreakable parts, small though they were, was taught and

thus such doctrines are really incomplete statements. For this reason, we take

the meditations of the Hinayana but not its

philosophical ideas.

Contrasting

again these attitudes, Mr. Chen said:

The Hinayana always speak only of dharmas and these they accept as ultimately real, whereas the Mahayana sees this earth

itself as without abiding entity; all the dharmas are

empty. Even in our bodies there is no self. Buddhists are agreed about that but

what about these things: noses and eyes, what is their true nature? The Hinayana seems to take up the self in the form of dharmas, into nirvana.

We will talk

later of the standards of choice to apply in selecting meditations and

philosophy in Buddhism. Therefore, when we meditate on this principle of the egolessness of dharmas, the

student should follow the philosophy of the sunyata school: Breathing

out touch the dharma (object); breathing in, think of sunyata.

Thus the two remaining sharp drivers are altogether finished.

2. Why follow

the above sequence?

Just because

we have finished the five meditations in the last chapter, where the main ideas

fostered were renunciation and impermanence, so first in this chapter we

discuss the rough meditations on the body, for this seems nearest to us.

Then, because

of the body's existence, comes the perverse idea of its beauty (subha). Dependent on this, we may experience loving

feelings. With the consideration of the feelings, we have progressed a little

inwards, for the body is "outside" compared with feelings. We should

then think about the painful things and not love the body. If the body can be

neither loved nor hated, then we demolish the second perverse view of seizing

upon extremes (antagraha). This we should accomplish

by truly knowing all feelings, both of love and hate, as sunyata.

Then Mr. Chen made a

simile for the progression of body-mindfulness inwards:

It is as if

one pursues a thief into the street. When he sees you after him, he hides in a

house doorway (feelings mindfulness). When you pursue him further, he hides in

a room inside the house. Thus we now come from mindfulness of feelings to

mindfulness of the mind. As the mind is impermanent—sometimes joyful and sometimes

sad, so one should meditate on its impermanence.

Following

this one should ask: who is the subject of mind? Here one pursues the thief into

the inmost part of the house: philosophically, one mindfully regards the dharmas to find that in them, also, there is no self.

Centering upon mind

and form with these four mindful meditations, nowhere is a self to be found.

When the perverted views are thoroughly uprooted with one's mindfulness

investigations, then this part of the process is finished. For these reasons,

then, our sequence is as we have described, progressing from gross to subtle.

3. The Four Mindfulnesses as a Totality

What does this

mean? To practice in this way, one combines these four into one meditation. In

the Hinayana, a meditator who is very skilled in samatha would be able to

meditate upon the smallest atom. Such is not our meaning here. Rather than be

sidetracked by a mindful enquiry into these subtle

particles, we should take them as sunyata and so rid

ourselves of the five sharp drivers.

Taken in this

aspect, the meditation on impurity is not only of the flesh, but concerns view

as well. This is to be reduced by sunyata meditation.

One is rid of the first sharp driver (the view of "my" body) thereby.

Why should we

meditate on the sunyata of feeling? All feelings are

usually grasped with the extreme view of them as pleasurable, painful, or

neither. But really they are all sunyata. With this

realization, the second sharp driver, the one-sided view, is destroyed.

Thirdly,

regarding the mind as impermanent, what does this mean? Impermanence implies sunyata. When one knows the sunyata here, then the third sharp driver relating to cause and effect is swept away.

Without meditating thus, the mind will always be looking for a source or a

cause.

In the fourth

meditation (on the dharmas) all the previous three

are included. This we may call "total samapatti."

The totality method which is described in some sastras but not taught by them as a bridge, is used by us in

this way to go from the Hinayana meditations across

to those of the Mahayana.

4. How to

Meditate Diligently on These

We are

advised by six similes on how to do this.

a. First: Just

as a thirsty person always longs for water, so we should meditate that we may

drink the ambrosia of sunyata to end cravings.

b. Second: Just

as a hungry person craves only for food, in this way we should meditate to

obtain spiritual food from our realization.

c. Third: Just

as a person overcome by the heat desires a cool wind, so we should meditate

that the heat of our desires lessens with the attainment of the cool of Nirvana.

d. Fourth: In

the cold weather, a shivering person wants the sunshine to warm him or her in

this way; we, devoid of wisdom, should meditate that the sun of wisdom may warm

us.

e. Fifth: One

who is in the darkness needs a lamp to see the way; so we who are in the

darkness of ignorance should meditate that our Way becomes clear to us.

f. Sixth: A

person suffering from the effects of poison requires some powerful antidote to

cure him; in the same way, we should meditate as we suffer not from one poison

but five and need the medicine given by the Buddha.

5. What

Perversion Each Meditation Cures

Human beings

always hold to the four inverted views, the first of which is impurity seen as

purity. This is cured by the first of the mindful meditations and then in order

follow: pleasure seen in pain (cured by the second meditation); permanence seen

in impermanence (destroyed by the third meditation); and, lastly, a self seen

where none exists (corrected by the fourth mindful meditation).

According to

the Hinayana, usual human ways of thought are

inverted, so they must first be turned right way up with, for instance, the samapatti on impermanence. Next comes the sublimation in

the Mahayana teachings of Prajnaparamita and through

the complete realization of sunyata, we can attain

the unabiding nirvana (sometimes called "the

true or great self"). This must be clearly distinguished from the higher

self postulated in Hinduism and Theosophy, since the teachings of sunyata enabling a Buddhist to reach this nirvana do not

exist in Hinduism (or indeed in any other religion). The Buddha only taught on

the "true self" just before his parinirvana (in the Sanskrit version of the sutra of that name), as a skillful means to enlighten his followers. We also should not mistake the Buddhist and

Hindu doctrines as the same. (See App. I, Part Two, A, 2.)

F. What Realization Can these Four Meditations

Bring?

1. Main

Realizations

a. The first

is called "warmth" because as sticks rubbed together become warm, so

these four meditations come near realization of the Four Noble Truths.

b.

"Top" is second. Here the meditations arrive at the "top"; samapanna is touched at this time, but the mind is still

liable to movement away from its objects. Sometimes the samapatti is settled, but at other times the mind wanders.

c.

"Patience." The mind should always conform to the topmost

attainment without moving. If it does not, then one's samatha is not yet strong enough to hold the samapatti without distraction arising, so at this time patience is needed. When

attainment is confirmed, then, patience is well developed.

d.

"The first in the world." When one attains this

stage it is possible to touch a partial realization of sunyata.

Such a one at that time is certainly first among all beings in the world.

2.

Realizations Related to the Three Liberations (vimoksa)

If the first

and third meditations are accomplished, then one will gain the signless liberation, because one does not seize the body as

a gross outward sign nor grasp at the mind as a subtle inward sign. The result

to be expected of the practice of the second meditation is the liberation of wishlessness, since one has concentrated upon the

painfulness of feelings, so that pleasant sensations are seen for what they are

and no attachment arises for them. Voidness is the

liberation gained from the successful meditation on all dharmas as having no self.

3. Other Realizations

If one always

meditates on the four mindfulness practices one will receive:

a. Increased

faith in the Dharma;

b. Power to

keep the sila very well;

c. Knowledge

of the truth of impermanence;

d. A real

renunciation;

e. Diligence

to practice always and not to be like counterfeit Bodhisattvas going here and

there; and

f. Increase

of wisdom (the meditation on the dharmas' having no

self particularly develops this).

G. Why among All the Hinayana Meditations Do We Take Only These Nine? How Are the Others Included in Them?

1. Let us

first consider the thirty-seven Bodhi-branches

(wings). All the factors among them may be reduced to only ten principles (this

reclassification was made by the Dharma-master Vasubandhu in his very learned commentary on the Kosa called "the

Buddha-upadesa sastra").

These ten are: mindfulness, tranquility, joy,

equanimity, morality, investigation, diligence, wisdom, faith, and meditation.

Now having

reduced these factors to their basic qualities, let us see how the nine

meditations include them all:

mindfulness

|

the four

mindful meditations themselves, particularly the third one

|

tranquility

|

samatha

|

joy

|

samatha

|

equanimity

|

samatha

|

morality

|

preliminary

stages

|

investigation

|

samapatti

|

diligence

|

sub-realization

|

wisdom

|

sub-realization

|

faith

|

sub-realization

|

meditation

|

the

meditation process itself

|

2. In the Abhidharma, a list of 40 meditations is given and these are

also contained within our five plus four. The forty are:

10 kasinas or meditations on colors and elements—these are included within our resolution of the elements

meditation;

10 impurity

meditations (cemetery meditations)—included in different aspects of our nine,

such as the exercises on the impurities and mindfulness of the body;

10

mindfulness of the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha (3 meditations)—included in preparatory chapters and refuge.

Mindfulness

of morality (sila)—preparation

Mindfulness

of giving (dana)—preparation

Mindfulness

of the gods (deva)—in the Mahayana, apparently,

instructions are only given to meditate upon the heavens, whereas the Hinayana is good in this respect, since if we remember the

gods themselves they will give us some help. We have emphasized their

importance in a chapter dedication;

Mindfulness

of death—included in our impurity and impermanence meditations;

Mindfulness

of the body (kaya)—included in our impurity and

impermanence meditations;

Mindfulness

of the breath—included in our impurity and impermanence meditations; and

Mindfulness

of peace—realization in samatha.

10 Miscellaneous

meditations for the development of the dhyanas:

4 divine abidings (brahma-vihara): two (maitri, karuna) included among

the five meditations, but the others to be considered later;

4 formless realms

(arupa dhyanas): as these

are found in other religions, they have been left aside;

Repulsiveness

of food: preparation;

Discrimination

of the elements: the third of the five meditations.

H. Why Will the Mindful Meditations Be a Bridge Across to the Mahayana?

1. This is so

because the four mindful meditations gather into

themselves all the merits from the practice of the five Hinayana meditations of the last chapter:

a. The body

is impure—merit from the practice of the first of the five;

b. All feelings

are painful—this includes the attainment of pity on others;

c. The mind

is impermanent—all the merits gathered from meditation on dependent

origination; and

d. All dharmas are without self—gathers the merits from element discrimination.

As these four mindfulnesses are always used in conjunction with the

breath, so the bridge is now complete and we may cross over.

We have now

passed across to consider the Mahayana meditations. Many classifications of sunyata exist, but I have selected these four where the

correspondence with the four mindfulnesses is both

close and striking:

a. From the

body's impurity, we go to the sunyata of self;

b.

"Feelings are painful" corresponds to the sunyata of others;

c. "Mind

is impermanent" aligns with non-dharma sunyata;

d. "Dharmas' having no self" to the dharmalaksana sunyata.

These

connections are not contrived, for there is a true and easily seen

correspondence. With our diagram this may be clearer. For these reasons we can

say that the mindful meditations truly form a good bridge (for these see

I. How Do They

Correspond with the Vajrayana?

The

correspondence here is of two kinds: with the lower three yogas as taught in

1. With the Japanese Tantra

Bodily

impurity is in the human body. In the practice of meditation, the human body

ceases to be experienced by the meditator who attains

success in samatha in the dhyanas.

One does not cling to the human body, and when it is meditated away, the

thought of its impurity also vanishes. What remains is a pure heavenly body.

Then this body has to be subjected to the process of sunyata sublimation in the Mahayana teachings. After this, no impurity remains either

in flesh or in spirit and the veils of sorrow and of knowledge are both gone.

All impurity, gross and subtle, is thus destroyed. In this complete process

through the three yanas, the Hinayana is in the position of cause, Mahayana is the sublimation-cause, and the

position of consequence is held by the Vajrayana,

when the pure body is transformed into a Buddha-body.

For the whole

system, then, the first two yanas may be considered

as causal, while the Vajrayana is of consequence,

where everything belongs to Buddhahood.

I must

emphasize to the readers that they should pay much attention to the two yanas of cause: To Hinayana purification and Mahayana sublimation, for without a firm basis of the practice

of their teachings, there can be no possibility of true attainment in Vajrayana. Without the first two yanas,

the third one becomes merely a matter of empty rituals and meaningless

mumblings.

This latter

is the "Vajrayana" of bad lamas who eat and

drink heedlessly, marry for pleasure, and who have little idea of the meaning

of what they teach, let alone any idea of practicing it. They should learn from

the example of our Lord Buddha, who preached and practiced all three vehicles

in his life. If the first two vehicles are not important (as some

"tantric" teachers suggest) then why did the Buddha teach them? Why

did he not directly preach the Vajrayana without the

other two? Out of all the thousand Buddhas in this

"auspicious aeon (Bhadra-kalpa)," only two

preach the Vajrayana. One of these was Sakyamuni and the other will be the Buddha to come after Maitreya (to be called Simhanada and now taking Bodhisattva birth as the Guru Karmapa).

Only two out of a thousand Buddhas care to give the Vajrayana teachings to the world; the others regard it as

too difficult for people to understand and liable to mislead the foolish.

But there is

no contradiction between these yanas, as some

suppose, the truth being that each one helps the next; therefore, not one of

them can be left out from our practice. Je Tsong-khapa,

to whom we have paid our homage, knew well enough the importance of

purification, an emphasis which many tantric teachers ignore.

Then, Mr. Chen said very

earnestly:

If one wants

to realize the Vajrayana, then one must first

practice the purification in the Hinayana.

Mr. Chen laughed,

saying:

Lamas marry;

which body do they use? It is plain to see that since so many children result,

it must be the body of flesh. If one practices the Hinayana meditations of purification, then through dhyana one

may acquire a heavenly, or refined, body. After the sublimation by sunyata in Mahayana, the flesh-body is completely

transformed into a wisdom-body, while by the Vajrayana practices this is transmuted into the diamond body of a Buddha. How then can a Vajrayanist marry for the usual purposes and have children

in the normal manner? Such is impossible for those who have passed through all

the purification processes.

After these preliminary

and general remarks, Mr. Chen went on to answer the question in the heading of

this section, showing the relationship between the four mindful practices and

the Japanese Vajrayana doctrines.

a. First

mindfulness

In Japanese Tantra there are five progressive forms of the Buddha-body

which correspond with the mindfulness of the body.

b. Second

mindfulness

After

purification and sublimation of feeling, then according to the third yoga

practice, the sixteen goddesses will come and make their offerings of rich and

costly things to the Buddha. At the time of practicing this yogic teaching,

feelings arise and, from the nature of the goddesses and their gifts, these are

certainly not painful, but are truly pleasurable.

c. Third

mindfulness

The teaching

of the Vajra-mind corresponds to the mindfulness of

mind. For its attainment, practice with both mantra and mudra is required.

d. Fourth

mindfulness

The

correspondence here is with the six element yoga practices.

All these

techniques will be described later (Ch. XII).

2.

Correspondences with Tibetan Tantra

a. First: in

the anuttara-yoga, the body is visualized as the

Buddha first in the growing stage (utpatti-krama),

where everything from the feet to the head is growing into sunyata,

so that every part of the body is taken into Buddhahood.

In the second stage, that of perfection (sampanna-krama),

all conditional parts of the energy and the entity of sunyata are identified in the perfected wisdom of Buddhahood.

b. Second:

practicing the meditation of tummo will result in

always feeling some ultimate joy in the Buddha-body.

c. Third: the

third mindfulness corresponds with the transformation of the mind into the

light of wisdom.

d. Fourth:

the fourth meditation has its correspondence when all dharmas are sublimated and become the mandala of the Buddha.

The group

above only corresponds with the first and second initiations of the anuttara-yoga. Taking the third initiation into account as

well, the four voidnesses and the four blisses should be added to correspond with the mindful meditations. (See Ch. XIII, Part Two, Chart.)

3. Breathing

Meditations

"We seem," said

Mr. Chen, "to have left aside the breathing meditations."

In the yanas of cause, breath concentration is only an aid to samatha, but in the yana of consequence, the Vajrayana, breath occupies an

even more important place than mind. Why? In the exoteric yanas'

doctrine, the training of the mind is always mentioned, and the energy

(especially bodily energy) is neglected. In the Vajrayana,

however, both are important, especially the aspect of energy. Why? In rebirth

within the six realms the eighth consciousness (alaya-vijnana)

appears to be the master. But what transports this consciousness? How can it

move? The answer is that movement takes place by means of the subtle life

energy which is bound up with the consciousness and cannot be easily separated.

All the innate or natural sorrow (sahaja-klesa) is

caused by this energy. (Note: this is purely a Vajrayana explanation, and nothing is said about it in the exoteric yanas.)

How does this

natural sorrow originate? It comes from the presence of avidya itself, which has been with us since beginningless time. It has always been with us, is difficult to destroy, and is held on to by

the eight consciousnesses. But in the Vajrayana,

there are some methods in the position of consequence (Buddhahood),

to transmute these natural sorrows and false views by the practice of wisdom-energy.

Therefore, in the Vajrayana, it is easy to get

enlightenment in this life. It is for this reason that so many methods concern

the breath. One may find these in our chapters on the Vajrayana.

"If we were to

enumerate and explain all the breathing doctrines," said Mr. Chen smiling,

"we would not be able to finish them tonight!"

In the Hinayana, detailed instructions for breathing practices

give fifteen methods. However, although these are good on their own level, they

do not even have the slightest flavor of the Vajrayana. Mindful breathing in the Hinayana progresses by way of the following stages:

Long

breathing in and out

Short

breathing in and out

Experiencing

the whole body through inhalation and exhalation

Tranquilizing

the bodily form

Experiencing

happiness

Experiencing

bliss

Experiencing

mental formations (samskara)

Tranquilizing

mental formations

Experiencing

consciousness

Gladdening

consciousness

Concentrating

consciousness

Liberating

consciousness

Contemplating

cessation

Contemplating

relinquishment

Contemplating

impermanence

All these

breathing meditations only lead one to partial attainment and, we may note,

they say nothing about complete sunyata. This,

however, we shall know well after studying the Vajrayana meditations on breathing.

One of the Tian Tai lists may also be given here for comparison (we

have already mentioned these sixteen excellences in Chapter III):

Know

breathing in

Know

breathing out

Know whether

the breath is long or short

Know the

breath pervading the whole body

Get rid of

breath-movements in the body

Experience

some happiness

Experience

some bliss

Experience

good mental feelings

The mind

generates some happiness

The mind

draws inside itself, becoming concentrated

The mind

experiences some liberations

Samapatti on

impermanence

Samapatti on

renunciation

Samapatti on

nonattachment

Samapatti on

distinguishing the Four Noble Truths

Samapatti on thorough

and perfect renunciation

J. Does the Vajrayana Also Include the Hinayana Doctrines?

The answer is

yes, definitely yes. In the Tibetan Vajrayana schools, many books and ritual instructions mention the four outward

foundations, and these are all taken from the Hinayana.

They are:

1. That

enough leisure for study and practice as well as a perfect body are both very

difficult to obtain. Here there is a correspondence with the mindfulness of the

body.

2. To

remember death, which comes at no certain time. This

foundation connects well with the meditations on death and impermanence.

3. That

causality is inexorable: "As a man sows, so shall he reap." The

meditations on dependent origination are connected here.

4. That in samsara, only pain is experienced: The correspondence with

the Four Noble Truths and mindfulness of feeling is plain to see.

I am very

sorry to note, however, that for most tantric rituals and doctrines, there is

only talk of the necessary preliminary practice of the exoteric yanas and very little practice of them. Too many Vajrayana gurus are inclined in this way; they talk too

much and practice too little. They could well learn from the Hinayana where practice is that while many scholars are

seen, there are few sages now. If the Vajrayana laid

more stress upon these four foundations and the meditations connected with

them, then it would be much easier for people to gain realization in the

disciplines of the

There is a

proverb in

"Among

any ten sages,

Nine belong

to Taklung-kagyu;

And of these

ten sages,

Nine out of

ten are poor."

This

points out to us that the great majority of those who truly have realization in the Vajrayana practice the renunciation and voluntary poverty

advocated in the Hinayana. Here indeed is the Hinayana in the Vajrayana.

K. What Are the Criteria for Choosing

Meditations from among the Three Yanas?

Meditators should

understand clearly why we have taken some meditations and left others in our

system of three-yanas-in-one.

1. Whatever

we take from the lower yanas must be found in

developed form in the higher ones. This is not merely my own idea but is based

upon the authority of ancient sages.

2. There

should be no conflict of philosophy between the lower and the higher. We should

select those philosophic teachings which lead us on from yana to yana. Thus in the Hinayana we appreciate highly the teaching of the Four

Noble Truths but we must put aside the incomplete Hinayana exposition of sunyata and nirvana. That is, in the

lower there must be something of value for the understanding of the higher.

3. Regarding

final truth, we should rely upon the teaching of the highest yana—the Vajrayana.

4. For the

preliminary foundations, it is proper to take them from the Hinayana.

5. According

to our three "C"s, we only take teachings

from the former two of cause and course, which will lead us onward to the third

one, that of consequence (Vajrayana).

6. Though we

take our doctrines from separate yanas, still our

whole scheme of three-yanas-in-one is systematized in

a natural sequence and is not according to any sectarian bias.

Concluding, Mr. Chen

remarked:

Some people

may want to use the various Buddhist doctrines in their own way. They might

first consider our system, try it out and see how it works, and then they may

change their minds. In any case, whatever systematizing is attempted, I advise

those who would do this work to base it on the above six criteria.

Our work

deals with the whole system of the three yanas; here

we have only begun with an outline of the nine meditations and all the

correspondences with the Mahayana and Vajrayana follow after. For this reason, no summary is made at the end of this chapter.

I most humbly

say that this is not the only systematic way and surely there will be others

who will do this work quite as well, if not better, than I have tried to do

here.

Then said the yogi:

"Nine o'clock." The writer counted the newly covered pages in his

notebook: Sixteen, this evening. And he thought: "Sixteen pages of

scrawled hieroglyphics to decipher and to convert into another chapter...."

May it be for the

increased mindfulness and consequent happiness of all who read it!

[Home][Back to main list][Back to Table of Contest list][Chinese versions][Next Chapter ][Go to Dr. Lin's works]