Buddhist Meditation

Systematic and Practical

CW35

Chapter X

A Talk by the Buddhist Yogi

C. M. CHEN

Written Down by

REVEREND B. KANTIPALO

First Published in 1967

Chapter X

HOMAGE TO JETSUN MILAREPA; PRAJNAPARAMITA, THE MOTHER OF ALL THE BUDDHAS; AND TO BHADANTA NAGARJUNA

Part One

ALL THE MAHAYANA MEDITATIONS ARE SUBLIMATED BY SUNYATA

Autumn had come to Kalimpong; yellow leaves were falling from the trees and the golden October sun shone warmly down. On this day, however, some dark clouds had gathered, the dark clouds of war. Throughout the morning jet fighters had been screaming through the heavens. The skies of Kalimpong, usually so serene, had become reminiscent of crowded English air near some air force base.

The boys in the vihara, and no doubt most local inhabitants, run out excitedly to see these strangers, but the listener and writer could well do without such disturbances, which remind them much too vividly of the last world-wide madness which people call "World War II." At that time and during all other wars, greed, hate, and delusion are at their strongest and most unrestrained. How much of the best in human culture was then destroyed, how many minds were perverted by hatred, corrupted by lust, or overwhelmed by insanity?

With such inward thoughts arising from the outward circumstances, the mind was turned towards meditative thoughts of our Teacher's fearlessness, as we approached Mr. Chen's Five Trees Hermitage. He had already announced that the subject would center about the prajnaparamita and its meditations. Could the contrast be greater? The insecure world boiling with the poisons and the tranquil perfect wisdom of crystal clarity. Would that more people learned this supreme way of disentanglement from the world, not wars but this medicine, antidote to all the poisons, this sublime perfection of wisdom.

A. Our Homage

"This is again threefold," said Mr. Chen.

"First, why do we honor Milarepa? His renunciation was complete, and besides this, he was accomplished in sunyata. He is a good example for us: both Hinayana and Mahayana combined in the practice and realization of one person.

Once he met two Buddhist scholars discussing sunyata. Neither of them had any true realization of the doctrines they were arguing about. He listened to them for a while and then asked them, "Do you think that rock is sunyata?" He pointed out a massive boulder.

"No, no," they said, "a rock is a very hard thing."

Then Milarepa, by the power of his practice, made his body penetrate that stone. He went through it and came out the other side as though that rock were a pool of water. After that, Milarepa asked the scholars, "What about the sky, is that sunyata?"

"Yes, certainly, the sky is empty," they replied. But Milarepa flew upwards, and sat down in padmasana in the sky as though upon the hardest rock.

"You see," he said, "it is a good seat for me."

One of the two scholars was converted to Milarepa's teachings by this personal instruction, but the other scorned him, saying that he was only a magic-monger and not a teacher of reasonable truth. Milarepa said to the latter, "You are quite right; you should keep to your doctrine and practice it. Later, when you have some realization, come to see me again."

As this great yogi was accomplished in both sunyata meditation and the power to renounce, we honor him.

To the mother of all the Buddhas, Prajnaparamita, we make our second obeisance. This is just the Dharma of sunyata personified and according to the exoteric tradition, there is no such being. However, since prajnaparamita is feminine in gender, because the Buddhas are produced by the Truth (that is, by the Dharma of perfect wisdom), so Prajnaparamita is like a mother to the Buddhas. In these ways, the outer teachings treat the perfection of wisdom. But in the Vajrayana, there are many descriptive texts for visualizing Prajnaparamita as a being, and here she is really regarded as the mother of the Buddhas. We must therefore offer her our praise and worship.

Third comes Bhadanta Nagarjuna, a great Buddhist philosopher very wise in the teachings of sunyata, who promoted the Vajrayana so well. His knowledge was not only theoretical, for he attained the Moonlight samadhi and, as you must know, the moon is a sign of bodhicitta (identified with sunyata).

B. What is the Distinction between Mahayana and Hinayana?

1. First come some negative explanations:

a. "Great" and "small" do not mean "inner" and "outer" in the sense of "inside" or "outside" the Buddhadharma. In China, scholars who criticize the Hinayana have usually maintained this, but I do not agree. The Hinayana teaches voidness and so cannot be called "outer." Ordinary humans, on the other hand, are truly "outside" the Buddhadharma since most of them hold to worldly happiness. It is said, in some scripture well-known among the Chinese, that in India there were 95 "outsiders" (doctrines outside Buddhadharma) and one "inner outsider"—the Hinayana. However, I do not agree that the personal teaching of Sakyamuni is an "outsider's" doctrine.

b. The difference between Mahayana and Hinayana is not that between right and wrong. Mahayana is Buddhism, Hinayana is Buddhism; and, as I must repeat, the latter was taught by Gautama Buddha in person. Some foolish people who call themselves "followers of the Great Way" have even gone so far as to regard the Hinayana as an enemy. It is they, not the Hinayana, who are wrong, quite wrong.

c. The difference between Mahayana and Hinayana is not that between earlier and later teachings. Even though historically the Hinayana seems to come first, while the Mahayana may seem a development, taken from the point of view of the whole system, we can see that this is really not so. In any case, nowhere is it said that when the Mahayana is fully developed, then one may leave aside the Hinayana. The latter should be taken as a foundation for the former. For example, the foundation of a building remains to support the walls and roof and is not taken away when the building is complete; thus it is here. What would happen if someone tried to remove the foundation after building the house? The answer to this question applies also in Buddhism.

d. These two vehicles are not the familiar and the remote. The Buddha's personal teaching of the Hinayana, of course, is very familiar. But the Mahayana doctrines are close to the truth of sunyata and so they also may be called "familiar." One cannot and should not distinguish them as near or far away. The reader should think for himself, "Which yana should I take first for study and practice?" That one is familiar to him, and the next, to which his practice of the first leads, is remote. This distinction, therefore, is between individual knowledge and practice.

2. Now we should give some positive explanations:

a. "Great" and "small" mean differentiation discerned on a basis of wisdom and merit. These two are compared by the Venerable Tsong-khapa to the feet of the Buddha, and neither one of them could be shorter than the other. In what sense is Mahayana great in wisdom? Mahayana wisdom is great because its teachings of sunyata are complete, whereas the Hinayana knows only a partial sunyata; therefore its wisdom is less.

A Mahayanist should know sunyata so well that he can penetrate to the void nature of all dharmas and so is able to use them in the conversion of sentient beings and for their general good; therefore, his merit is great.

The follower of the Hinayana lays more stress on samatha, keeping the silas very seriously, so that often his merit may be insufficient to benefit all beings. For instance, on an occasion when evil must be used to convert beings, he would be unable to help them, adhering strictly to the rules of morality. Or again, a Bodhisattva following the Mahayana might well decide that it was for the good of five hundred to kill one, and he could do this, but a Hinayanist could never do such a thing. Hinayana merit, therefore, is small compared with that of the Great Way.

Tsong-khapa said in his great work on the Tantra that the difference between these two is only a matter of merit, but I cannot agree with him. The venerable teacher says that both in Hinayana and in the Mahayana the doctrine of sunyata has been taught, so that in this respect they are equal, but practitioners of the latter perform many good works for sentient beings and so acquire much merit: they are contrasted with the practitioners of the Hinayana who have not done so many meritorious deeds and have in consequence not enough merits to attain Buddhahood.

There are few points here for comment:

i. It is said in the Yogacarya Bhumi Sastra of Maitreya that "the wisdom of sunyata is a good source for the expedient means proceeding from the bodhicitta." It is proof to say that if sunyata is recognized as complete, then merit is much increased, compared with the Hinayana where merit is less, since sunyata is incompletely understood.

So the nature of sunyata is the same, but the area which sunyata pervades, as well as the method and function deriving from sunyata are much greater in the Mahayana. While we must differ from Tsong-khapa regarding the depth of voidness to be experienced in the two vehicles, still we agree with his estimate of their merits.

ii. Tsong-khapa says that the Hinayanist has not done as many good deeds as the bodhisattva, so the merit of the former is smaller. Why has he not done so many good deeds? The great Dharma-master should admit that this is because his Hinayana wisdom is not sufficient for him to see the necessity of so much action. That this is true, we may see from certain situations requiring the exercise of evil as skillful means: the Hinayanist would not be able to do that, and the many, therefore, would not be saved. Suppose that a lady passionately implored the love of a Buddhist—a strict Hinayana follower could only give her a morally elevating discourse (which might or might not be accepted) but a bodhisattva who is already accomplished in sunyata and in Hinayana teaching might acquiesce to her demands, teaching and converting her in the process.

The writer here requested that Mr. Chen tell a story he had mentioned once before about the skillful means of a bodhisattva. Mr. Chen then recounted the following:

Once collecting alms a bodhisattva passed before a house. A girl came out to give him some food, and, seeing his noble appearance, fell in love with him. So strong was her passion that she immediately invited him to follow her into the house. The bodhisattva, through his power of penetrating the minds of others, knew her desire and did not consent, quietly going on his way. As he went he thought, "As it is now, she will just continue to lust after worldly pleasures and so go from bad to worse in the realms of samsara. Supposing I were to go back and do as she wishes, but at the same time convert her?" So he went back and had intercourse with her, living with her for some time. At first, she found great pleasure in sexual union but after a time the bodhisattva began to change his organ into a knife. The girl found that her former pleasure became painful, and the bodhisattva was able to preach to her on the unsatisfactory nature of all existence. Pleased at, and convinced by, his preaching, the girl renounced her household life and became a nun.

If the bodhisattva had only adopted Hinayana methods, then she could not have been converted as by these means. Only good people (who in any case will come to the Dharma sooner or later) can be saved in that way. But it is necessary to look out for the others, the evil ones who are unable to help themselves and by their own unaided efforts cannot find salvation.

It depends on wisdom; if this is great, then there is much merit and no hindrance. So I have emphasized merit and wisdom: both great—Mahayana; both small—Hinayana.

b. The second positive reason: while in the Hinayana one does of course find alms giving, morality, and patience all stressed very much, still these are not present in the sense of paramita (See Ch. VI, B, 1, a. iv) because they are not understood with the complete sunyata of the Mahayana. For this reason the Hinayana is rightly so named.

c. The Lesser Vehicle follower aspires to liberate himself, to free himself from the sorrows. Only one person is considered; therefore, Hinayana is correctly so named.

What is great here? The Mahayanist tries to develop the great bodhicitta to benefit others. A bodhisattva should have such a function from sunyata as to take the five small poisons of human beings and transmute them into the Great Poisons of Buddhahood. Names such as Great Pride, Great Lust, Great Ignorance, etc., (and all are characteristic of Buddhahood) are written in the Manjusri Name and Significance of Reality Sutra and are praised there by that bodhisattva. (This is explained in Appendix I, Part Two, A, 4.)

d. Through the "sublimation in sunyata" doctrine, the bodhisattva ascends to the Diamond Way, where Full Enlightenment in this life is possible. To do this, one requires a teaching praising great courage, and such is the Mahayana. But the Hinayana teaches only the small courage necessary for the attainment of arhatship. With this small courage, one is far from Full Enlightenment; this is useful only to carry one on to the Mahayana from which the final vehicle can be followed.

In making these distinctions, I have no bias, and no sectarianism between these yanas. What has been set forth here will be seen, if examined carefully, to be quite fair.

C. Mahayana Is not Negativism and the Six Paramitas Are not Merit-Accumulations for Going to Heaven

1. Even a scholar as famous as Takakusu treats the prajnaparamita philosophy as negativism—a common mistake. In China the San Lun School, which was based upon the Three Sastras (Madhyamika Sastra and Dvadasanikaya Sastra, both by Nagarjuna, and the Sata Sastra of Aryadeva), used these works just for the purpose of argument and the nature of their propositions were negative in form. They employed these sastras and their contents just for argument but we have quite a different purpose; we shall use them as the bases of meditational practice.

The eight negative conditions formulated by Nagarjuna are excellent as a means of investigating the truth, and they are also good principles for refuting outsiders and converting them to Saddharma. Besides this, they have a practical value which directly concerns us—they are good formulas for samapatti upon the truth when, after continual negation, one gains the position of consequence and positive truth appears naturally. So from this point, their value is very definitely positive, not negative, and it is quite wrong to regard them as only the latter. Despite this, ancient and modern scholars have all treated these statements as negativism, not giving any meditations upon them, only theories. So tonight we shall give some meditations not to be found in any book.

Prajnaparamita itself should not be confused with the San Lun School which existed only to study this corpus of texts and to engage in dialectic battles, but not as a practical school with methods of meditation. Contrast this with Bhadanta Nagarjuna, who not only used his philosophy to debate with outsiders, but also applied it to meditate on truth, and he was fully accomplished in sunyata realization.

As a complete contrast to Nagarjuna, we may cite the example of Xuan Zang: although he was deeply learned in the Yogacara School and of course knew of its meditations, still he did not practice them and had no realization of them. Just after translating Prajnaparamita he died (but from this work, of course, obtained some blessings).

From all this we may see that sunyavada is a positive philosophy, not merely a negative dialectic, when it is actually practiced in meditation.

2. When merits are always accompanied by realization of sunyata, they become very great; they are, in fact, then transcendent merits. Accompanied by sunyata, merits do not produce results in the worldly heavens but produce fruits for the great Bodhi path leading to nirvana.

Nowadays there are many good persons who do not understand this. They perform actions according to the first three paramitas, but if they do not act according to meditation on sunyata, then their merit will only carry them into a higher state in samsara. They may think that they are bodhisattvas but really they are not; they are just the same as common men who do something good to get to heaven.

To give an example: in two almsgivings of the same quality and quantity, the merit of a donor with the force of sunyata meditations to accompany his actions will accumulate to aid him onwards to nirvana. The other, who lacks this, must go to heaven for his deeds. Whether one will get rebirth in heavenly states or attain nirvana is entirely according to one's knowledge and meditation of sunyata.

3. The four boundless minds have been left aside so far, as they belong to mathematical, not to philosophic, boundlessness. In the Hinayana, it is admitted that they are meditations for heaven, not even for arhathood. In their practice, there is still a subject (one who practices) and an object (the person toward whom one practices), and the good deeds one does (the friendliness, compassion, etc. cultivated), and all this leads to heavenly attainment.

With the realization of sunyata it is quite different. The subject is void, the object is void, and so too are all the deeds done; consequently, the merits are not for heavenly fruit. Such is Mahayana practice of these boundless minds.

D. The Practical Methods of Mahayana Sunyata Meditations

I have arranged these into four classes:

1. Meditations of sunyata—here there are four methods.

a. First meditation: To meditate according to the four phrases found in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra:

"Not born from a self,

Not born from another.

Not born from both,

Not born without a cause."

When the practitioner has attained a good posture and achieved some firm attainment in samatha, he should then think of these four phrases. The last one is very important, but one should only practice it after having inquired into the first three. From inquiry into them, one will not get any answer (though wrong views will be successively cut down), but at the fourth stage one will realize sunyata, which is not only negative but will be manifested from the gathering of many conditions.

b. Second meditation: Meditation on the eight negatives. These are:

No production (utpada), no extinction (nirodha);

No annihilation (uccheda), no permanence (nitya);

No unity (ekartha), no diversity (anartha); and

No coming (agama), no departure (niragama).

Here we should distinguish what is the purpose of these opposite arguments. In the first two, we find the nature of nirvana clearly defined. Is this not enough? Why should we proceed to the other pairs?

First, we should confirm the meaning of nirvana; that is: "nir" means "no production," and "vana" is "no extinction." How then do we come to the second pair? Some persons agree with the first two statements but hold a wrong view either of the extreme of annihilation or of permanence. For them, this second statement has been formulated to point out the errors of these extremes. Particularly strong is the wrong view of permanence, but if something exists which is permanent now, then in the past also it must have been stable, for one cannot have impermanent permanence. But if we examine closely all our knowledge, we do not find any support for permanence— all, in fact, is impermanent. This second pair, besides refuting these extreme views, is also useful for the attainment of the nature of conditions in sunyata.

Why, then, "no unity, no diversity"? This is because some persons have the idea of monism, that from a One First Cause, all the many things have their source. But the many things with which we are acquainted in samsara are continually changing, so how can their origin remain unchanging? Is it possible to have a relationship of an unchanging One First Cause and the ten thousand changing things? This pair is used to show the inconsistency and untenability of such a position, thereby refuting the non-Buddhists who hold it.

Why does one next come to the statement "no coming, no going"? Some persons do not like to formulate their religion philosophically; they only have blind faith in a Creator God. We have come from him, and, so they say, if we believe in him we will go back to him. To save those holding this false view and to correct their blind faith, one should use this pair of opposites.

But all this is for conversion and debate, as indeed it was used by the scholars of the San Lun School. Of course it is good for these purposes, but what is its possible application for our meditations? The answer to this question is not to be found in any ancient book, but in my opinion it is like this:

For the first two: If one meditates on these (after, of course, completing the preparations given in the previous chapters), then one will get some sign of unabiding nirvana. If this is an extinction, there can be no production of a sign. But then one who has realized this nirvana comes to some function of salvation, and then it cannot be called "no production." So this pair of opposites is identified in unabiding nirvana.

Regarding the second pair: If one meditates on this, one will gain some practical knowledge of the nature of causation. If causes do not accumulate, then nothing can be produced, and then there is annihilation; but if causes are collected together, then some function will occur from their interaction, and then there is permanence (continuity of function). Function according to conditions is changeable, but according to the laws of cause and effect we cannot call it "annihilation."

On the third pair: When we meditate on this and get some attainment we shall know how to abide in the same entity with all sentient beings. Then it is possible to develop the great compassion of the same entity (See Ch. X, Part Two, 5 and Ch. V, C, 5) which arises without reference to specific conditions. Too many scholars studying sunyata doctrines neglect compassion, so one should practice this meditation to see that others are not the same as one in conditions, yet are not different from one in entity. In this meditation, one recognizes the same entity but at the same time sees that "you" are "you" and "I" am "I."

"But," said the yogi with real compassion, "one recognizes this same entity but so many others do not—one feels great pity for them."

As for the fourth pair: This is to gain an insight into simultaneity. If one meditates on this pair, then one gains freedom from the limitations of time, for we must know that all the three times are the same entity in sunyata. Truth is to be found in a fourth dimension beyond space and time, and if we would know it, we must free ourselves from their limitations. Time, after all, is quite relative—today is the yesterday of tomorrow, and is also the tomorrow of yesterday. In sunyata meditation, the three times all become the same and besides knowing well the present, one may easily have foresight into the future, or cause the events of the distant past to be remembered in the present—as Lord Buddha often did. For such a one there is no limit; he can make the future into the past and the past into the future, and many wonderful supernormal powers occur.

These are the possibilities for our own meditation but nobody has given instructions like these before. One might well ask: "Why?" To me it is very surprising! There have been so many "bodhisattvas" but they have not set forth such meditations.

Mr. Chen laughed at this strange circumstance and then repeated:

Surprising, yes! And difficult to understand. There was, as we have mentioned, the sutra and sastra study school for the prajnaparamita but not one school devoted to its practice. Such a state of affairs is very extraordinary and I am sorry to have to report that it is so. Therefore, we must set up such meditations for the real practitioners who wish to follow the Way.

c. Third meditation. The four voidnesses are listed in the diagram in Chapter IX, and regarding these the first meditation is on the sunyata of self, the second on the sunyata of others, while the third concerns the sunyata of non-dharma and the fourth meditation is on the sunyata of dharmalaksana.

While there are many classifications of sunyata, some present it from too many aspects which may be confusing to the neophyte while others give it under one or two headings, useful only for the wise: this classification of sunyata has neither too many nor too few aspects and fits well into our scheme of the three-yanas-in-one.

To explain this further: First, one investigates oneself and cannot find there any abiding entity—one is void of self in both body and mind. For the next meditation, one looks into what is other than "myself." This refers to other people, all of whom are seen after examination to be devoid of self. One looks at people with whom one has widely differing relationships and notices that whether it is one's wife who is beloved or one's enemy who is hated—all are sunyata in their nature.

Non-dharma voidness, upon which one next meditates, includes many spiritual events occurring during meditation, such as the appearance of a light or the hearing of a voice. Even such insubstantial things as these, together with time, direction and other non-material dharmas—all these are found to be sunyata.

Finally, the fourth meditation, on dharma-form, applies to all the material dharmas—form, color, and so on—these, too, are all void in their nature. Under these four aspects every phenomenon has been included and, with practice, their void nature can be known, but we must beware of the mistake of thinking of them simply as nothing.

d. Fourth meditation. The last method is the meditation on the mind in the three times, for neither in the past, nor in the present, nor in the future is the mind attainable. This meditation is given according to the Diamond Sutra.

These four meditations are on the nature of sunyata but not on its conditions, so now we come to a consideration of these:

2. Meditations on the Dependent Conditions of Sunyata

a. Fifth meditation. This is according to the translation of the Diamond Sutra made by Kumarajiva (one of the six translations of this sutra into Chinese and probably the most well-used and popular). Six similes are given which illustrate our point; while in other translations more than six occur, still these seem to be quite sufficient. One should think about all these six things as manifestations of sunyata and neither regard them as nothing, nor as "things" possessed of self or essential nature. These are suitable for neophytes to practice, and they are easy to meditate upon either after the completion of the Hinayana practices, or to be used alongside them.

(The following are from the Diamond Sutra, translated by E. Conze.)

"So should one view what is conditioned:

"As a dream": There is nothing one can hold to when one awakens after a dream, but still one may remember some of its details. The voidness of its nature is the inability to grasp anything therein; and the fullness of its conditions is having such conditions gathered which produced that particular dream.

"As an illusion": A magician produces some phenomena which to ordinary people, not knowing his methods, may seem to be real; this is the fullness of conditions. If you examine carefully what he is doing, unreal—this is the voidness of their nature.

"As a bubble": Outside, it is round as a ball, but inside quite empty. The outer appearance is the fullness of conditions and the inside the voidness of nature. In the Vajrayana, this particular method is further developed in meditations on the body as a bubble.

"As a shadow": Our shadows never leave us and we can see them quite plainly but cannot ever catch them. Seeing that they have happened is their fullness of conditions while being unable to catch them is their voidness. Reflections in a mirror are very similar to this example.

"As dew": Dew is like a bubble, quickly comes and quickly gone. When it has happened, it is clear and wet, but when it dries, there is nothing remaining. Even when we see cleanness and wetness, its fullness of conditions, these contain within them the possibility of drying—and this is its void nature. This is a good example for impermanence related to sunyata.

("As Lightning" is the sixth simile; but the original text does not contain a paragraph here on this.)

b. Sixth meditation: Meditations according to the Ten Mystic Gates of Hua Yan. These meditations are suited to skilled practitioners and are not for new students; only the former can gain through them the understanding of mystic causation. They have been established by the Venerable Du Shun, a great enlightened monk and an emanation of Manjusri. We will talk about his teachings in the next chapter.

These meditations upon mystic causation, if practiced to attainment level, are productive of many supernormal powers. Why was it that the Buddha possessed such ability with these? Because no subtle fetters remained to block their development as he attained to the full length, depth, and breadth of sunyata and all mystic conditions had fully gathered in him.

In order that the reader might at this stage understand a little of what is meant by this term, Mr. Chen demonstrated two instances. He said, "Through the eye of a needle the greatest mountain may be seen complete with all its snows and rocks," and then holding up one finger, he emphasized, "and this is the height of the highest of peaks!" Then he spoke a little on the famous Buddhist simile of Mount Meru and the grain of mustard seed. That little seed contains neither more nor less sunyata within it than the whole of the highest mountain at the center of the Buddhist cosmos; that peak contains all voidness and in it all the Dharma-nature is to be found.

Upon another occasion, the yogi related the words of an ancient Dharma master who answered the question of a Confucian scholar and governor of that province, puzzled about the same enigma of the mustard grain and Mount Meru, in this way: "You have studied and remembered so many books all of which could not be stored in one room, but you have managed to store them all in your small skull. How?"

3. Meditations on the Karma of Great Compassion Coming out of Sunyata

a. Seventh meditation. Following from one's sunyata meditations, meditate upon the victorious significance of the bodhicitta. We know three kinds of bodhi-heart, the first two of which are also possessed by the Hinayana; they are the bodhicitta of will and that of conduct. The third one is found only in the Mahayana and is described as sunyata which is the source of the bodhicitta. From the entity of the sunyata, we know the nature of the Dharmakaya; we know that every person has the same Dharmakaya. As a result of our realization, we are, so to speak, joined into the same body with all sentient beings. From this Dharmakaya, no one may be excluded, not even wicked persons. From this realization arises the great compassion unconditioned by thoughts of individuals.

This compassion is a very important condition for the first three paramitas, and if one has not experienced it, these perfections cannot be completed. For what reason should I give alms? From compassion based upon the Dharmakaya. Why should I maintain a pure morality? Realization of this same Dharmakaya. Under all circumstances, why should I be patient? All beings share this same Dharmakaya, and knowing this one can have nothing but compassion for them.

The Bible has a passage illustrating my meaning rather well (although they do not know the Dharma-body and refer here to flesh):

"But now are they many members, yet but one body. And the eye cannot say to the hand, I have no need of thee; again, nor again the head to the feet, I have no need of you." (1 Corinthians 12:20-21)

The body spoken of here is one of flesh, but we are talking of the Dharmakaya in the sunyata sense. This example is just for ease of understanding and does not illustrate exactly the same thing.

If one meditates thus, the bodhicitta will increase and one will do everything with patience.

b. Eighth Meditation: To meditate on the three wheels of every action (trimandala) according to the sunyata doctrine.

The example often given was then quoted by Mr. Chen:

When giving alms, the subject, the object, and the thing given, each of these three "wheels," should be seen as void. That is to say, no giver is anywhere perceived (as we have meditated upon sunyata of the self), no one is seen who receives the alms (since we have meditated on the sunyata of dharmalaksana), and no essential nature is seen in the object given.

These same three wheels are applicable to all the paramitas, and indeed they are not fully perfected unless this trimandala applies to them quite naturally. They should also be applied to every action in life, not only while one is seated in meditation. One should meditate upon everything in this way until this becomes a habitual tendency of the mind. Supposing that after meditation one intends to take lunch: the "I" that is going to eat is void, the food to be eaten is also void, and the method of taking it is also void; all three are sunyata. It may be easy to remember this method if one thinks of the three as parts of speech, that is, subject, object, and verb; giver, receiver, giving; eater, food, eating; etc.

The cultivation of this aspect of sunyata is quite necessary for the complete fulfilment of the first three paramitas and, as I have warned before, without the wisdom to perceive this, one only accumulates merits to go to the heavens. If there is any thought of "my merit" or "the good of others," then this indicates that one has no proper attainment in sunyata, for a real sage has no such ideas.

4. Meditations on Breathing and Sunyata

Two different methods may be given:

a. Ninth meditation: breathing with the action of the bodhicitta. When breathing out, one distributes all one's merits to others; while on the in-breath, all evil, painful things are drawn into the body and the force of them is used to destroy the concept of self within. This is a good practice to gather both merit and wisdom.

b. Tenth meditation: Breathe out—do not think of any dharma. Breathe in—do not think of any skandha.

Outside no self; inside no self. The breath itself is sunyata; it is mind, it is wisdom; at this stage do not make any distinction; all should be identified. When one attains to stopping of the inner energy, then one should no longer think about "in" and "out," just carry on the sunyata meditation, concentrating undistractedly upon it.

The ten meditations, on the four classes into which we have divided the practical method, are now finished.

"And here," said Mr. Chen, consulting his watch and flicking over the many more pages of his notebook covered with closely written characters, "also we shall have to finish. If we try to complete the chapter tonight, you will still be writing at twelve o'clock. This chapter should be divided into two parts, of which this is the first."

We stepped out in to a starlit night. A thousand diamonds shone down upon us and the Ganges of the sky wound its luminous way from one horizon to the other. All was very vast, empty, and silent, a sight appropriate to our subject—may it long continue as peaceful.

Part Two

SUPPLEMENTARY DETAILS OF THE SUNYATA MEDITATIONS

Before meeting our Yogi at the "Five Leguminous Tree Hermitage" the listener had been manifesting considerable Buddhist activity in Kalimpong while the writer had been sitting quietly inspired by reading the late Venerable Xu Yun's "Song of the Skin Bag," just published in a Buddhist magazine.

Upon arrival at the Hermitage, both were ready to hear Mr. Chen's words. He spoke as follows:

A. Commentary

Already we have talked upon four practical sections of the sunyata meditations. Now we come to some supplementary details of the nature of a commentary on the above.

1. All the meditations we have spoken of belong to the meditations classified as Utterly Beyond the World (see Ch. III, C, 2, c).

2. We should know with regard to our definition of Buddhist meditation (Ch. III, Conclusion): "... and transform it from being abstract perception into a concrete inner realization whereby liberation from sorrows and false views (and the) embodiment of nirvana are attained." What was said there all applies to these sunyata meditations in the Mahayana.

The sunyata doctrines were mistaken as abstract principles and taken as useful only for refutation of non-Buddhists; meditation was not practiced to make them into a concrete realization. But the reader has the chance to do this, as these meditations have now been constructed for him. Our readers, however, must pay attention: it is very important to understand the phrase in our definitions concerning "abstract made concrete," and to make this process clearer we shall talk about it here at some length. (See this Part, 5.)

The final phrase also requires a word or two: How is the embodiment of nirvana attained? Nirvana is the entity of sunyata and one who realizes this attains to nirvana.

3. The four "boundless minds" are processed through the sunyata meditations and converted from infinity in a mathematical sense to a true philosophic boundlessness. By way of this processing, they become identified with the Dharmadhatu, which is endless, since it is without space limitations. To convert them in this way, they must be associated with the practice of the first three paramitas and the functioning of the bodhicitta.

4. All the sunyata meditations outlined here correspond with the nine Hinayana meditations of the last two chapters. How? In this way:

Correspondence of Hinayana and Mahayana Meditations

1. The "four unborns" correspond to "all dharmas without self" (9);

2. The "eight negatives" correspond to "discrimination of elements" (4);

3. The "four voidnesses" correspond to "all dharmas without self" (9);

4. The "unattainability of mind in the three times" corresponds to "mind is impermanent" (8);

5. The "six similes of the Diamond Sutra" correspond to "dependent origination" (3), "all feelings are painful" (7), and "the body is impure" (1, 6);

6. The "ten mystic gates of sunyata according to the Hua Yan School" corresponds to "the twelve nidanas of dependent origination" (3);

7. The "victorious bodhicitta" corresponds to "the merciful mind" (2);

8. The "three wheels of sunyata" corresponds to "all dharmas without self" (9);

9, 10. "Breathing with sunyata" corresponds to breathing as taught in the Hinayana (5).

(For easy reference, the ten sunyata meditations, numbered, are shown above with their corresponding Hinayana meditations numbered one to nine.)

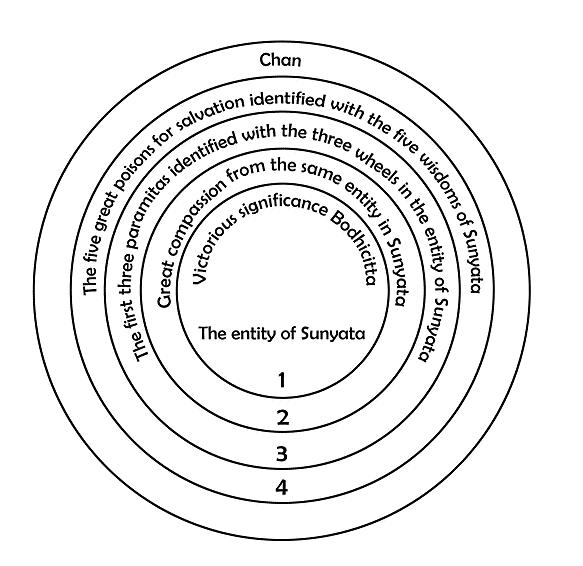

5. Here we should explain our diagram. This one is explained by the simile of a stone thrown into a calm pond. The waves resulting from such an action are then explained as follows:

a. First Circle. From the entity of sunyata arises the victorious significance of bodhicitta. Why does this come first? Because the victorious significance is sunyata itself; hence in the diagram these two are shown within the same circle. Why bodhicitta? Because sunyata is the nature of the Dharmakaya and this is the entity of all sentient beings (including the practitioner himself) and upon this relation of identity arises the bodhicitta without other worldly conditions. This is the first becoming of sunyata.

Sometimes when one's meditation is inspired by the Dharmakaya, then one may even weep; this comes neither from sympathy nor from pain but from this kind of bodhicitta in sunyata. After Full Enlightenment, the Buddha himself recognized that every sentient being occupied the Dharmakaya, but their minds not being in this sunyata meditation, they failed to recognize this fact. So there emerges from the bodhicitta a great compassion for them. All this is within the first ring-wave of sunyata.

b. Second Circle. From the bodhicitta as source and with the realization of sunyata comes out a wave, a wave of the great compassion of the same entity. This compassion is only great and only produced in those who attain to sunyata; otherwise it is only the merciful mind with reference to specific beings. The attainment represented by this circle may be held while in sitting practice, but not when one is going about one's activities. This is the second becoming of sunyata.

c. Third Circle. Acting out in one's life the first three paramitas in perfect relation to the three wheels of sunyata is possible for the nirmanakaya Buddhas alone. But the bodhisattva, who must do everything for beings, indeed should practice over a very long time. Hence the bodhisattva takes a very long time to reach the final attainment. Even a wisdom-being good at meditation practice, and already upon the third and fourth stages (bhumis—see end of chapter) must do everything for everyone well—accompanied by patience, and from so much activity, naturally, many obstructions are produced. This will continue to be his position until the eighth stage is reached, when a bodhisattva gains the patience of the unborn sunyata and may then do all these things easily. The new bodhisattva is one in name only, or rather in great good will and determination only, even though he has bodhicitta. Bodhisattvas who are nowhere near the eighth stage, indeed not yet attained to the first, are too inexperienced to accommodate the "three wheels" closely with the three paramitas. Their meditation force is not strong enough, and this makes the wisdom-beings' faring a long one, very long.

While recounting this aspect of bodhisattvas' progress, Mr. Chen wept, evidently recalling this not merely as facts learned from books, but from his own experience. "We come, then," he said, "to the fourth circle."

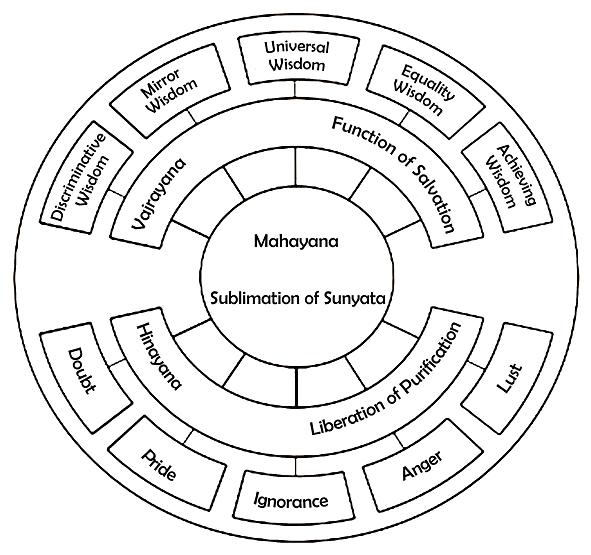

d. Fourth Circle. In this, the foundations of salvation are enlarged and the five poisons are used, well-accompanied by the five wisdoms (see also "vajra" diagram). One who seeks the functions of Full Enlightenment must take a progressive way and come to the Vajrayana. The time taken to achieve perfection is lessened and the way of salvation, to final success, is shortened.

Knowing the above progressions of sunyata and practicing them, there can no longer be any sense of "abstract." From successful practice will come a "concrete realization."

6. If one recognizes all these meditations very well; that is, if one only gets some knowledge, some good right view, even apart from accomplishment, then just this alone is a very rare thing, very precious.

But one must hold these teachings in the mind so that the balancing forces of mercy and wisdom are identified. Most people are one-sided: if they lack wisdom, they may be merciful; whereas the wise may be weak in compassion. In our meditations on the bodhicitta good nature or compassion is balanced with the clever or wise aspect.

Elizabeth Wordsworth has a little poem to illustrate our point.

The writer here disentangled the following lines of this English jingle from amid the complexities of a page of Mr. Chen's notebook packed with Chinese characters:

"If all the good people were clever,

And all the clever people were good,

The world would be nicer than ever

We thought that it possibly could.

But somehow 'tis seldom or never,

The two hit it off as they should;

The good are so harsh to the clever,

The clever so rude to the good!"

It shows, in a worldly sense, that the good and the wise tendencies in man are not properly balanced. Through the meditations described here a little recognition of both these ideas will be gained and thus they may be harmonized.

In Tibet, there is a warning about these two things: one is told on the one hand to hold the highest idea (or the sublime theory), while the other is to hold to the widest good (or ample bodhisattva practice), and to have either without the other means that they have not been identified.

Here is a good story on this point, and the yogi proceeded to relate:

In the Yellow Sect (Gelugpa), there is always much emphasis placed on the acquisition of merits by the doing of many good works. Once there lived a bhiksu following the tradition of this school who had done very many good deeds and had practiced for a long time the ritual of Avalokitesvara Mahasattva, but in spite of all his labors, he had not realized sunyata. It is said in the very instructions which he so diligently practiced that as the rituals and meditation are interconnected, so, by the performance of one side, the other would be realized. Still with so many merits accumulated, he had not yet any realization. One day he was printing the sutra of Avalokitesvara, when suddenly he made a vow:

"If what the books say about merits is true, then when I throw up this printing block, may it stay up above my head! If the truth is otherwise, may it fall down." So he threw the carved block up into the air and immediately there appeared the great bodhisattva Manjusri who reverently received the block into both his hands. The bodhisattva then addressed the good bhiksu, saying, "I never left aside merits in my wisdom. I was never parted from them. Go on, you should go on!" At that moment the bhiksu attained to realization of sunyata.

This is a good story for us, and shows us that Avalokitesvara, the great bodhisattva of compassion, was never parted from wisdom, while Manjusri, the mahasattva of wisdom, never left aside merits.

Some person may ask me, "I have not yet been able to identify these two principles, so which way—that of wisdom or that of compassion—should I practice first?" I should answer in this way: if you have wisdom enough, just follow the course of meditations found in this book. If your wisdom is not sufficient yet to recognize these meditations as the right way, then first engage in the performance of many good deeds for the accumulation of merits, after which you will get a great increase of understanding.

B. Daily Meditations for Both Hermit and Ordinary Meditator

1. Firstly, for the full-time practitioner of meditation, I have organized the hermit's practice-times with meditations in the following order:

Early morning practice—2 sittings

(1) Breathing with the action of the bodhicitta (9)

(2) Breathing on no dharma, no skandha (10)

Before noon—3 sittings

(3) The four unborns (1)

(4) Karma of great compassion (7)

(5) Eight negatives (2)

Afternoon—3 sittings

(6) The four voidnesses (3)

(7) Three wheels (8)

(8) Ten mystic gates of Hua Yan (6)

Night—2 sittings

(9) Unattainability of mind in three times (4)

(10) Six similes of the Diamond Sutra (5)

Thus all the sunyata meditations are arranged within one day of the meditator's practice. Notice that it ends with meditation on the simile of the dream. The meditator should hold on to this until he enters a dream state and recognize it, even while he is dreaming, as sunyata. These meditations are specially balanced to include both meditations on the sunyata of nature (voidness) and on the sunyata of condition (fullness).

The scheme outlined here is for the person in whom the tendencies for wisdom and compassion are more or less balanced, but it should be adapted in the case of those having one-sided characters. Thus, if a person has more wisdom than mercy, let him replace the four unborns (1) and the unattainability of mind (4) by greater emphasis on the karma of great compassion (7) and the three wheels (8). In one who is opposite in nature, having more compassion than wisdom, he should not meditate on the three wheels (8) and concentrate more upon the four voidnesses (3). Thus should be the hermit's practice.

2. If we consider the ordinary person with no time to spare for hermit life, how should he be advised? First, he should get up a little earlier than most people, at least half an hour (and preferably more) before others wake up or he will be disturbed by them. He should close his room as though it were a hermitage and instruct his family that he is not to be disturbed by them for any reason whatsoever. They should not even knock on his door and in any case be careful to keep quiet. First then, he should make some offering to the Buddha such as the traditional candle, incense, and flowers, and then kneel down and humbly worship the Enlightened One three times; after that, he should recite the following confession and entreaty:

And our yogi wept as he recited this to us:

"I am sincerely sorry. I am just like a deer with many wounds from a hunter; such are my many unskillful deeds. Please keep me, O Exalted One, safe from the beasts of prey of greed, hatred and delusion for at least a half-hour."

"During the day, I am like a dog forever biting upon a dry bone and getting nothing but the blood of my own lips. I ought not to live in this way but I have no choice as there are others in the family to support. So many of my hours are as the dog's concern with the dry bone—wasted—but my time now is of real benefit. Please help me and protect me so that I may be able to renounce this fully."

Very earnestly, he should continue:

"I am like a little maggot in a cesspool, for all day long I do nothing but pursue excrement: my time is given over only to the gain of worldly wealth. Please help me to receive some spiritual food so that my meditation may progress to the attainment of enlightenment."

After his puja, which should establish him in a good state of mind for meditation, he must sit in the position as we have described before (see Ch. II, A, 4). A short time with earnest meditation and concentrated endeavor is much better than a lifetime spent as a hermit in name only, that is, lacking proper conduct.

As regards this lesson, the ordinary person should take these meditations in rotation, maintaining the same sequence as we have given here. Before commencing each meditation, one of the breath-and-sunyata practices should be practiced for a few minutes to gain a deep samatha. As there are two of these meditations, they may be used as preliminaries on alternate days. Thus there will be a complete cycle of these meditations every eight days.

C. Why Do We Say that Mahayana Meditations are Sublimated by Sunyata?

This is because if the wisdom of sunyata can be attained, one will get the realization of Buddhahood. Even if we cannot meditate on sunyata, we may gain some intellectual understanding of Full Enlightenment and still recognize what is to be sublimated. In this sublimation process, the Buddha-nature will get rid of the five illnesses or errors.

1. Five negative errors corrected:

a. One will completely get rid of the lowest mind, for once one knows the Buddha-nature then one occupies it oneself.

b. One also gets rid of the proud mind towards those of lower caste, class, or occupation. Such people also have the Buddha-nature, so what distinction can one make?

c. All vacant maya-like volitions, which mistake the false for the real, will be given up when one knows that every person possesses the Buddha-nature.

d. One will not say anything bad concerning the Dharma or deity. No abuse can come from your lips once you have known the Buddha-nature.

e. You will not hold to a "self" of any description once the Buddha-nature is realized, since it is non-self.

2. Furthermore, from these meditations there are five positive virtues to be gained:

a. Right diligence. Some persons, although they are diligent, make effort only for self-centered aims and objects. While one's diligence is of this kind, one will not get to the goal for a very long time. If it is right diligent practice for the Buddha-nature and therefore Dharma-centered, then neither time nor energy is wasted. Perfect diligence is possessed by one who knows the Buddha-nature.

Sadly, even most Buddhists do not recognize the Buddha-nature and only do good things for the benefit of what they mistakenly believe to be a "self." As this is so, their goal can only be the heavens.

b. Right reverence to the Three Gems. An ordinary person worships a God or gods just for his own advantage, or else to benefit what he thinks of as belonging to "himself" (family, etc.) However, one should not blindly worship gods for selfish motives, but rather know the Buddha-nature; when this is accomplished, then one will obtain from it an incomparable blessing of power into which no self or selfishness enters.

c. If the Buddha-nature is recognized, then one knows also prajnaparamita. This is the opposite way around to our meditation on the perfection of wisdom.

d. One will attain some mundane wisdom. That is, wisdom connected with the world but not of the world—wisdom of the conditions of sunyata (fullness), not of the nature of sunyata (voidness).

e. One will generate a great merciful mind. That is, the compassion of the same entity naturally arises when the Buddha-nature is known.

3. Further, we should understand our progress in a systematic way and with the help of the diagram in the Chapter IX.

From the purification of the Hinayana in the position of cause, one passes through the Mahayana meditations in the position of course, where insight into the Buddha-nature is obtained, to come finally to the ultimate position of consequence in Vajrayana, Buddhahood. This is the whole system of Enlightenment. Now we are at the second stage, and the second stage and the third will come in our chapters on the Vajrayana.

We have this diagram, therefore, (see Ch. IX) where the correspondences of these yanas are explained. The relation of the four mindfulnesses is like this:

Mindfulness of the body: Through sunyata sublimation becomes the Buddha's body with the impurities of the former transmuted into the purity of unabiding nirvana.

Mindfulness of feelings: Through sublimation, the painful feelings are transmuted into the pleasure of unabiding nirvana.

Mindfulness of mind: its impermanence is sublimated by sunyata experience to the permanence of the Dharmakaya.

Mindfulness of dharmas: "All dharmas have no-self" is transmuted into the Great Self of nirvana; through sublimation, they become the karmas of the great mercy performed through the bodhicitta.

("Great Self" here is not the conception similarly named and found among the Vedanta Hindus. In the case of the latter, the process of sublimation in the fires of the sunyata meditations is absent. Only after penetrating the nature of voidness is one entitled to speak of the "Great Self" of nirvana.)

Bhante Sangharakshita added: "After all, 'self' is a word, and all words are relative. Buddhists, therefore, should not be afraid of this word."

These changes all depend upon the Buddha-nature of sunyata, which is like a great furnace, and out of the fire of wisdom are born these sublimated elements of Mahayana realization.

Bhante interjected between Mr. Chen's words that this was the true alchemy, for the results of which so many fruitlessly sought in so many wrong directions.

D. How to Transmute These into Vajrayana Meditations in the Position of Consequence

Again, we refer the reader to the diagram of the four mindfulnesses.

1. The Body is Impurity. This process continues through the stages of the Hinayana where it is considered from the point of view of impurity, death, the corpse meditations, etc., to gain detachment from it, and through the attainment of dhyanas performed upon these objects, to gain a purified meditative body. Next one proceeds to the Mahayana body. Through its sublimation in sunyata meditations, it has become a cause of the Dharmakaya: one has then come to the Vajrayana. The Tantras give expedient methods in the consequence position of Sambhoga Buddhahood.

One of these is in the Japanese Tantra where five signs of a Buddha-body are taught (See Ch. XII, F) and one practices meditation on them visualizing one's transmuted sunyata body as possessing these five. It is the experience of Buddha himself. The visualized Buddha is in the position of consequence, so that when one really succeeds in meditation, one becomes this Buddha. This process is found only in the Vajrayana, and in the initiations (abhiseka) necessary before the meditations of this vehicle may be practiced, one is told these secrets in the position of consequence. Such secrets are only the Buddha's treasure, and I stress that there are only a few who can understand; they are exclusive, and for very few persons.

In the anuttara yoga of Tibet there are not only five signs of a Buddha visualized in the heart, but also a thorough practice with all parts of the body. The growing and perfecting stages of anuttara yoga are all performed on visualizations of the body. In the lower tantras there are only five signs, and these, though important, are not enough. Anuttara yoga goes into great detail, so that sunyata is realized in every part of the body. All parts of the body have meditations upon them: the eyeball, for instance, is sunyata, and even inside one tiny body-hair, the void nature is to be clearly seen. Sunyata is the Buddha-nature, so if anything remains in which sunyata is not seen, then one has not the Buddha-body.

Then with great emphasis, Mr. Chen said:

If one has not passed through the sublimation-stage of sunyata meditations in the Mahayana, then Vajrayana visualizations become just like magic of delusory nature, and certainly one does not possess that which is quite devoid of delusion, a Buddha-body.

The process with the other three meditations is similar and the remarks made on the body's successive transmutations apply also to them. As we will have a chance to talk about them in the Vajrayana chapters, there is no need to dwell upon them here.

E. About the Five Poisons

1. Now we have come to the Vajra diagram. The poison of lust is treated with meditations designed to show its impurity. After this cure, one does not lust again, but in turn treats this purification to the meditation process through sunyata so that one comes to know that in its nature, the poison of lust is also void. The selfish poison of lust is fundamentally negated in the purification process, but the "unselfish poison" in sunyata may be used positively as a function of salvation for those still affected by the selfish poison of lust.

This particular poison corresponds to one wisdom of Buddhahood—the mirror-like wisdom. One's body is like a reflection in a mirror. Every mirror will reflect a face or body whether it is beautiful or ugly. Beauty, purity, and their opposites arc all seen as sunyata with this mirror-like wisdom, which reflects their true nature. As far as the nature is concerned, all forms are both pure and void. Though they may appear to the discriminating mind (which has not yet realized sunyata) as wrathful or beautiful; to one who knows sunyata, no such notions remain: only the mirror-like wisdom appears.

In brief, in the Vajrayana, where the function of salvation is stressed, the Great Poison of lust united with the Dharmakaya has some connecting function to save persons full of common lust.

The four other poisons follow this same pattern of sublimations followed by functions, and the details need not be repeated here. (For definitions of the Great Poisons of Buddhahood, see Appendix I, Part Two, A, 3 and 4).

F. What Are the Realizations of Mahayana Meditations?

We have said that we only choose our meditations and doctrines from the yanas of the first two "C"'s, but not from the last one (see Ch. IX, X), so we should not talk here of the ten states of the Bodhisattva path which are in the position of consequence for us, since they are still to be realized.

There are two views in Tibet regarding the practice of these ten stages. The Yellow Sect says one who practices the Vajrayana must first pass through all of them. The Old Schools differ, maintaining that not all the stages are necessary and, though technically they must be passed, they may not be very clearly defined in the practitioner's experience. After all, the Mahayanist takes three kalpas (aeons) to complete his bodhisattva path while the follower of the Adamantine Vehicle may progress from unenlightened worldling through all the stages of the bodhisattva path to Buddhahood in just one life. It is as if two people, going to the same place, choose differing forms of transport. Here the Mahayanist is like a person traveling by train: every town at which the train stops will be clearly seen by him. The Vajrayana, however, may be compared to the latest jet airliner, and one traveling by this vehicle has only a blurred impression of the country below him.

Thus, in my opinion, these two views do not contradict each other. If a person for many lives has already followed the Mahayana, he may very clearly experience all the ten stages with their different characteristics. But for one who is just newly initiated into the Vajrayana with little or no practice of the Great Way in previous lives and therefore having only a short time as a bodhisattva, these stages may not occur so clearly. Yet in both cases, the goal of Full Enlightenment is the same.

We will now show readers something of these ten stages, but we do not say that they have to pass through all of them before getting to the Vajrayana. Remember, we are only taking teachings of cause and course which will be useful for leading us into the full attainment of Buddhahood, so as these stages have not yet been realized, we cannot describe them as methods useful for practice. But in the Vajrayana it is admitted that providing a man has developed the bodhicitta of the first stage, still he may go on to the Diamond Vehicle and practice there. The attainment of the first stage is a matter of great difficulty requiring persistent effort through one aeon, so one intending on Full Enlightenment should not be discouraged but, without waiting so long, should press on with the methods offered by the Vajrayana.

G. Why Are the Ten Stages So Named?

1. Paramudita (Great Joy). After arrival at this stage, the new bodhisattva will gain a practical knowledge of the deep meaning of sunyata which he had never experienced before. As a result he will obtain great ecstasy—hence the name of this stage.

2. Vimala (Purity). When the bodhisattva comes to this stage he renounces impurity, because even the finest faults cannot be committed after his experience of the force of sunyata. Thus he is free from defilement as the name suggests.

3. Prabhakari (Illuminating). This stage is so called because the bodhisattva obtains samadhi with the ability to hold dharanis (long incantations to various Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and deities), and is then pervaded by an infinite wisdom-light.

4. Archishmati (Flaming Wisdom). The bodhisattva who reaches this stage has obtained success in sunyata and the fire of wisdom which burns up all sorrows has been established from his concentrations upon the thirty-seven Bodhi-branches.

5. Sudurjaya (Difficult to Conquer). Some expedient methods are very hard to perform by experience of sunyata. One who reaches this stage is freed from such difficulties.

6. Abhimukhi (Appearing Face to Face). What has appeared? The identity of good conduct (merits and compassion) and sunyata is clearly seen by one. At the stage one makes great efforts to investigate by samapatti all the good deeds he or she has performed and finds that throughout they are void and formless.

7. Duramgama (Traveling Far). In this stage one seems to be on a very long journey into the distance, all the time pressing on without either stopping or forcing oneself. The bodhisattva easily comes close to the pure unity of the function of sunyata (for one aspect of this, of a group of ten given in the Hua Yan philosophy, see next chapter).

8. Achala (Immovable). Because one does not hold to form and retain in every form, and acts without force, not moved by the sorrows, thus this stage is called the Immovable. The sunyata of the patience of the unborn is obtained at this stage.

9. Sadhumati (Good Thoughts). In this stage, one may preach freely to everyone and rid oneself of all obstacles.

10. Dharmamegha (Dharma-cloud). At this time, the bodhisattva's gross, heavy body becomes as wide as the sky. The Dharma-body is perfected and just as there may be many "clouds" in the sky, so he or she becomes one of these and endlessly rains down Dharma.

After the Tenth Stage comes the time of Full Enlightenment of Buddhahood when the two veils of passion and of knowledge are altogether gone.

H. Why Are There So Many Stages in Sunyata?

Someone might object: you say that sunyata means voidness, so how can there be different degrees of it? This depends on the depth of wisdom, which may be shallow or deep, and the realization varies accordingly. So now we shall give a list of realizations of the ten bhumis together with what remains to be done.

1. In the first stage, bodhisattvas are very skilled in the practice of patient understanding, and by this they realize that the true nature of dharmas is that they are non-born or non-produced. But they cannot rid themselves as yet of committing subtle faults, and these blemishes may sometimes occur in spite of their exalted state. The first-stage bodhisattvas should practice sunyata further, as they have not thoroughly identified the whole mind with the energies. Their right view is developed, but many small aspects of conduct are yet to be perfected.

2. With right recognition and the careful performance of everything they do, bodhisattvas may rid themselves of the small blemishes. At the second stage, they lack, however, equanimity in sunyata regarding worldly matters, nor do they know the dharanis. They should make more progress.

3. At this stage bodhisattvas can hold the equanimity mentioned above and have obtained the dharanis but still cling to a fine attachment to the Dharma. They should release themselves by further practice of sunyata meditations, so that they may progress to the next stage.

4. Here bodhisattvas are able to renounce their love of the Dharma, but hold to practice of samapatti on the Dharma-nature. Sometimes they fear birth-and-death and are still afraid of two extremes: the loss of nirvana and falling into samsara, and that nirvana is too far away and completely unobtainable by them. Fearing these two extremes, they cannot practice the Bodhi-branches of upaya (skillful deeds) so they should strive onwards to the fifth stage.

5. When bodhisattvas get there, they cannot abide in the meditation of no-form which they used to rid themselves of the two extremes. They must make efforts to pass on to the next bhumi.

6. When they practice non-form in the sixth stage, sometimes they are rid of that difficulty and sometimes not. They fall between non-form and lack of non-form. They must progress again.

7. At this stage, bodhisattvas manage to get rid of the function of non-form without forcing, but then come to the freedom of form and they cling on to this. Therefore, they should go on to the eighth stage.

8. Though they do not now cling to the freedom from form, still they are not yet skilled in distinguishing all forms, sentient beings, and doctrines. These three they cannot properly discriminate—and so cannot be good preachers of Dharma. For this, they should make progress to the ninth bhumi.

9. Thus they come to next to the last stage, in which they are very skilled in preaching, but the Dharmakaya is not yet perfected and realized face-to-face. Hence they should go forward to the tenth stage.

10. Although they now realized the perfect Dharmakaya, still a little subtle jneya-varana (veil of knowledge) remains. Because of this they lack a little of the transcendent wisdom and mystic views.

When these are gained, bodhisattvas come at last to Buddhahood. These are the reasons why there are so many stages in sunyata.

I. What Is the Realization of the Various Stages in Detail?

1. In the first stage a bodhisattva can:

a. Attain 100 kinds of samadhi;

b. See 100 Buddhas;

c. By his or her supernormal powers, know 100 Buddhas;

d. Move in 100 Buddhas' worlds;

e. Pass and look through 100 Buddhalands;

f. Preach in 100 ordinary worlds;

g. Gain long life up to 100 kalpas;

h. Know all events in the past and future within a span of 100 kalpas:

i. Enter into 100 Dharma-gates (methods of Dharma);

j. Appear in 100 bodies;

k. Surround his or her main body with 100 mind-produced bodhisattvas as a "family"; and

l. Be Dharma-lord of Jambudvipa.

These are the twelve merits of the first stage of a bodhisattva.

2. In the second stage the attainment is 1,000-fold of the first.

3. 100,000-fold of the first.

4. Million-fold of the first.

5. 1,000 million-fold.

6. 100,000 million-fold.

7. 100,000 million nayutas-fold.

8. 100 million times the amount of dust-particles from 3000 great chiliocosms multiplied by the attainments of the first stage, plus being the Dharma-lord of 100 worlds.

9. As above, but Dharma-lord of 2,000 worlds and receive samadhis to the number of all the dust contained in 100 million asamkhyeyas of countries.

10. Ineffable-fold. This word "ineffable" is not an objective word with the usual meaning but a proper name of a vast number in Buddhism. It is said that a bodhisattva at this tenth stage can obtain samadhis of the enormous number of all the dust-particles in 100,000,000,000 nayutas of Buddhas' realms.

J. What Realization Should We Have before Entering the Vajrayana?

In my opinion, in following the Mahayana Path, before we get to the First Stage, there is only some feeling insight (Ch. III, C, 2, c) from the practice of meditation.

But if we have known all the experiences listed below, then the Vajrayana may be entered. It is much better to practice first the Hinayana and the Mahayana rather than plunge straight into practice in the Diamond Vehicle. Even though one's training is not yet completed in these yanas of cause, still one may, provided that good foundations for practice have been laid, go on to the Vajrayana, because there also some doctrines of the Hinayana and Mahayana are mentioned. It must be admitted, however, that most Tibetan teachers do not pay much attention to them and this neglect of the lower yanas should NOT be imitated elsewhere.

As we have mentioned before, the first stage of the bodhisattva path need not first be attained before making a start with the tantric teaching, but all the following experiences, which are much easier to come by, should be known by one undertaking tantric methods:

1. In the wisdom gained through practice, one attains some right view of sunyata. This is very important, we must emphasize.

2. One should at least recognize (but not necessarily realize) the sunyata of conditions mentioned in the Hua Yan teachings while practicing the samapatti on the Dharmadhatu.

3. He or she should recognize Gong An (koans) in the Chan School.

4. One should know how expedient means of Bodhi come from sunyata wisdom.

5. One neither hates samsara, nor loves nirvana.

6. After practicing sunyata meditation, one's body has become somehow superfluous, and one no longer always identifies the body with "himself" or "herself" and so is not attached to it.

7. In his or her dreams things are seen covered only by a paper shell, inside which there is nothing. Or again, he or she may be always flying in dreams as the body has become very light after sunyata realization.

8. One experiences the merciful mind arising from the sunyata wisdom.

9. There is no doubt on the profound view from which one may gather the widest good conduct. One knows sunyata and merits without the doubts illustrated by the good bhiksu in our story.

10. All the first three paramitas become very easy to perform.

11. One sees everyone only as shadows.

12. Not much attention is given towards worldly reputation and wealth, and such things as gain and loss affect one very slightly.

13. Though one does many good things which benefit others, one does not cling to such deeds as merits.

14. One has been inspired by the eight different groups of gods and is protected by them. In this way one gains the conditions to help others.

15. One receives from the wisdom of non-guru some direct instruction.

16. One always feels light and at ease both in mind and body.

All these are not attained in the first bodhisattva stage, but one who has practiced as I have outlined here will already be inspired by his experience of sunyata acquired through the Mahayana meditations. If all these sixteen experiences are attained, they are quite sufficient as a foundation of sunyata to go on to the Vajrayana.

And after such a lengthy and thorough chapter on The Wisdom Which Goes Beyond, what more could be said?

(Note well: Nobody should try these meditations without first practicing the purification meditations given in Chapters VIII-IX; attempts to practice sunyata disciplines without proper guidance may well be dangerous.)

[Home][Back to main list][Back to Table of Contest list][Chinese versions][Next Chapter][Go to Dr. Lin's works][Related works: Mahayana Meditations]